Imagine, now, an ashen-faced Roderick Usher strumming casually on a lute and speaking in hushed tones to his newly arrived visitor, Philip Winthrop (Mark Damon):

Imagine, now, an ashen-faced Roderick Usher strumming casually on a lute and speaking in hushed tones to his newly arrived visitor, Philip Winthrop (Mark Damon):

“ . . . sounds with any degree whatsoever [fill] me with terror . . . I could hear you coming—every footstep, every rustle of your clothes. I could hear your horse approaching, hear the clatter of its hooves across the courtyard. Your knock—the grating of the door bolt—was like a sword stroke to my ears. I can hear the scratch of rat claws within the stone wall.” (And the last sentence is spoken in the lowest possible whisper. Highly effective.)

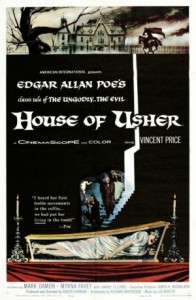

As Roderick Usher, Vincent Price has one of the signal roles of his career in The Fall of the House of Usher, clearly the best of the eight Poe-inspired horror films Roger Corman made between this first entry in 1960 and Tomb of Ligeia in 1965. The budget for House of Usher was much larger than for most American International films—still paltry by other studio standards—and the images convey a deceptive opulence. The first of two color films among these five horrible old movies, the screen is deeply saturated with shades of gray, brown, red and green, with Usher’s often bright-colored wardrobe and white hair accentuated against drab halls, crudely plastered walls and rickety staircases.

As in Night Monster, the house is a major player in the film. With its cracks and settling noises, it is isolated in a desolate countryside and stands in the midst of, to quote Edgar Allan Poe, a “silent tarn—a pestilent and mystic vapor, dull, sluggish, faintly discernible, and leaden-hued.” Usher describes the polluted, dank lake, how it was once clean and bright, with gliding swans and animals that came down to drink. He adds, “But that was long before my time.”

In a macabre moment in the film, Usher, with candle held aloft, shows Philip the gallery of family villains—thieves, harlots, mass murderers, victims of madness, bizarre paintings created by the late Burt Schoenberg. Philip has come to take away Madeline (Myrna Fahey) as his wife, a desire which arouses Usher’s warnings that she, too, suffers from his hyperesthesia and, as will be seen, also shares his hypochondria. Beneath the house is the crypt, claustrophobic and cobwebbed, where Madeline gives Philip a tour of her own, showing the tombs of her ancestors—and the one empty coffin that awaits her.

Richard Matheson wrote the House of Usher screenplay, based on Poe’s 1839/40 tale, as well as scripts for some of the subsequent Poe/Corman enterprises—The Pit and the Pendulum, Tales of Terror, The Raven, etc. The writer is perhaps most famous for his sixteen scripts for Rod Serling’s early ’60s Twilight Zone TV series. Stephen King said of Matheson: “He was the first guy that I ever read who seemed to be doing something that [H. P.] Lovecraft [1890-1937] wasn’t doing. . . . It wasn’t eastern Europe—the horror could be . . . just up the street. . . . And to me, as a kid, that was a revelation . . . He was putting the horror in places that I could relate to.”

Richard Matheson wrote the House of Usher screenplay, based on Poe’s 1839/40 tale, as well as scripts for some of the subsequent Poe/Corman enterprises—The Pit and the Pendulum, Tales of Terror, The Raven, etc. The writer is perhaps most famous for his sixteen scripts for Rod Serling’s early ’60s Twilight Zone TV series. Stephen King said of Matheson: “He was the first guy that I ever read who seemed to be doing something that [H. P.] Lovecraft [1890-1937] wasn’t doing. . . . It wasn’t eastern Europe—the horror could be . . . just up the street. . . . And to me, as a kid, that was a revelation . . . He was putting the horror in places that I could relate to.”

Les Baxter achieved his greatest fame as the leader of his light music orchestra—there is his mega hit of 1956, “Poor People of Paris”—and his score for House of Usher is strangely unmemorable. He scored many of the other Poe/Corman films, over a hundred films during his career, and most of them have this same “memorability.”

Points of interest: Harry Ellerbe, who plays Bristol the butler and is easily the best actor after Price, had an even smaller role as a minister in The Haunted Palace (1963), supposedly part of the “Poe/Corman” series but actually based mainly on a story by, coincidentally, H. P. Lovecraft, and—how’s this for a small world?—the screenplay was by Charles Beaumont, who created even more of Serling’s Twilight Zone scripts than did Matheson.

My apologies for lingering on the Corman flick. It’s been a favorite since its première.

My apologies for lingering on the Corman flick. It’s been a favorite since its première.

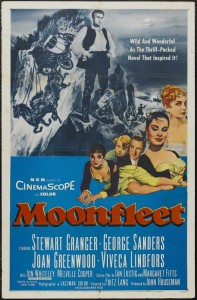

As has the next entry in these ongoing horrible old movies. And please forgive me for not seeking, again, a masterpiece, a milestone, a great effort in the genre. This next flick is certainly not in that category. It’s not exactly a horror film, more like a costume drama, or maybe a romance, or a swashbuckler, none of which it is long enough or successfully enough to be anything in particular, but it does have horror elements—a graveyard, a skeleton in a shattered coffin, a smuggler’s cave and, most important, an old house.

It would seem, in 1955, that Moonfleet had much going for it: art director Cedric Gibbons (The Wizard of Oz, Mrs. Miniver), producer John Houseman (The Bad and the Beautiful, Lust for Life), costume designer Walter Plunkett (Gone with the Wind, Young Bess) and cinematographer Robert H. Planck (Little Women, Royal Wedding). Though in Eastman Color, the tints and hues have some of Technicolor’s vivid richness.

Yes, quite impressive, these credentials: all the more surprising since the endeavor turned out so—well, so uninspired and uninspiring. And director Fritz Lang’s name conjures up an assumed greatness which simply was never there, at least not in his post-German films, though he struck sparks in America with Scarlet Street and The Big Heat. But no sparks in Moonfleet, maybe a few flickers.

One of the better boy-actors, Jon Whiteley carries the weight of most of the picture, much as Bobby Driscoll does in Treasure Island—and remember Walt Disney’s low regard for Driscoll? Whiteley plays John Mohune, who arrives in Moonfleet, on the Dorset coast of England, in search of Jeremy Fox (Stewart Granger). Fox first wants nothing to do with the boy, but a camaraderie grows between them; Mohune, even, develops an instant puppy-like attachment, calling him “my friend.” The eighteenth-century period is that of Scaramouche (1952), which also starred Granger, and the actor—costume, hair style and performance, even the hip boots—could easily have stepped unchanged onto the Moonfleet set.

The biggest plus for the film is Miklós Rózsa’s music, another example of superb and conscientious work expended on a weak film, much as Erich Wolfgang Korngold gave his best to second-raters Escape Me Never and the remake of Of Human Bondage. Rózsa, along with a few other veterans of the ’30s and ’40s, persisted in writing copious, wall-to-wall scores, even when the vogue in the ’50s dictated sparse music or ubiquitous title songs. That so many cues were rescored, some even deleted from the final cut, reveals both Rózsa’s perseverance and the film’s problematic evolution.

After an agitated, three-note motif, repeated over the M-G-M and CinemaScope logos, the single main title theme has an English folk song flavor; all is seascapes, waves crashing onshore. Film and music come together most effectively in scenes in the graveyard, a smuggler’s cave and the rundown Mohune Manor. In the opening, the boy comes across a cemetery with an eerie-eyed angel statue and is captured by a band of smugglers, the first of much sinister music. That three-note motif and the main title tune are cleverly interwoven and varied throughout a score that also includes period-appropriate music, a passepied and a bourée.

Rózsa delivers, in fact, the best score among these five films, especially remarkable in these sequences:

In another scene in the cemetery, Mohune falls through a hole into the smugglers’ cave and discovers their boss is Fox himself. The boy dislodges the casket of the notorious Redbeard and among the scattered bones finds a locket and, inside, a list of Bible verses with incorrect chapter/verse numbers. Fox realizes the numbers are ciphers for the location of the long-lost, long-sought Redbeard treasure. Working together, and with Fox masquerading as an officer, they access a garrison and there, lowered in a bucket into a well, John finds a diamond.

In another scene in the cemetery, Mohune falls through a hole into the smugglers’ cave and discovers their boss is Fox himself. The boy dislodges the casket of the notorious Redbeard and among the scattered bones finds a locket and, inside, a list of Bible verses with incorrect chapter/verse numbers. Fox realizes the numbers are ciphers for the location of the long-lost, long-sought Redbeard treasure. Working together, and with Fox masquerading as an officer, they access a garrison and there, lowered in a bucket into a well, John finds a diamond.

Joan Greenwood, with her mahogany voice, is Lady Ashwood. She makes several passes at Fox, even in the presence of her husband, George Sanders in a typically slimy role. Viveca Lindfors’ severe coiffure, hair pulled tightly in a bun, and darkly slanted eyebrows are highly off-putting, and, indeed, her persona is not a sympathetic one, a weak and, as it turns out, discarded woman.

John Mohune is the film’s only sympathetic character. So naïve and trusting is the boy, that despite Jeremy Fox’s ill treatment of him, and though Fox has sailed away mortally wounded (unknown to the boy), John is confident he will return because, in the last line of the film, he says, “He’s my friend.”

Points of interest (expanded!): Among the notable supporting players, including Alan Napier, Melville Cooper and John Hoyt, there are some old reliables who tend to disappear in the shadows: Ian Wolfe, who seems to have made thousands of movies between 1934 and 1990 before his death at age ninety-five; Jack Elam, with the out-of-kilter eye; and the emaciated-looking Skelton Knaggs, who died a few months before Moonfleet was released.

Excuse a digression here, though still appropriate to this genre of film. Knaggs appeared in The Ghost Ship, House of Dracula and Terror by Night, but a boyhood favorite is his Gilly character in Blackbeard the Pirate. A sawbones (Keith Andres) is removing a pistol ball from Blackbeard’s (Robert Newton) neck, and the pirate says, in that dawdling, “arr-r-r-ing” voice, “Gilly, Gilly, give him just a tickle with the point of your bla-a-a-a-de, at about his liver-r-r-r.” Had to include that!

you are right about moonfleet but you are all F-up about the others as they are classics and will be here long after you