Sometimes there’s a terrible penalty for telling the truth.

Sometimes there’s a terrible penalty for telling the truth.

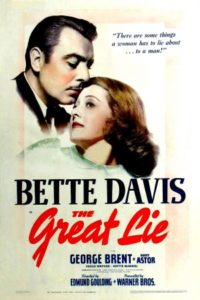

Time not only ages all people and some art, it also has a nasty habit of distorting memory. Warner Bros.’ 1941 The Great Lie is a case in point. I had probably last seen the film—no, not at the premiere!—in my growing-up years in the 1950s and had only a modest recall of it when I recently DVDed it.

Wow! Not the film I remembered—not that, however foggy the memory, I had ever regarded it as exceptional, even out of the ordinary. It is neither. Perhaps the problem is time itself. Acting standards have changed, much more so have racial values, and what was regarded as sophisticated, even daring, in 1941 now seems embarrassingly antiquated and unrealistic. An unwed mother turns no heads today. Actually, that “shame” hardly seems a concern in the film; rather it’s the lie about false motherhood that receives the emphasis.

The Great Lie is, first and worst of all, a soap opera—predictable and implausible, clichéd, seething with pseudo-drama and character loathing. Unlike most soap operas on TV today, the acting is, if not outstanding, acceptable, more than outstanding in the case of [intlink id=”1045″ type=”category”]Mary Astor[/intlink], who steals the show. Quite a coup considering [intlink id=”603″ type=”category”]Bette Davis[/intlink] is her co-star.

Maybe the implausible, convoluted plot can be briefly summarized. Let’s try. New York man-about-town and aviator Peter Van Allen ([intlink id=”1483″ type=”category”]George Brent[/intlink]) is supposedly newly married to bitchy concert pianist Sandra Kovak (Astor). In his choice, he has passed over wealthy young Maggie Patterson (Davis), an off-and-on-again girlfriend, a kind of bosom buddy confidant.

Maybe the implausible, convoluted plot can be briefly summarized. Let’s try. New York man-about-town and aviator Peter Van Allen ([intlink id=”1483″ type=”category”]George Brent[/intlink]) is supposedly newly married to bitchy concert pianist Sandra Kovak (Astor). In his choice, he has passed over wealthy young Maggie Patterson (Davis), an off-and-on-again girlfriend, a kind of bosom buddy confidant.

But no matter. Seems Sandra wasn’t properly divorced from previous hubby. She and Peter must remarry. He flies to Maggie’s Maryland farm to tell her. His arrival in his biplane excites her and Violet (Hattie McDaniel) and the other African American servants. Only he doesn’t tell her. (Brent was a licensed pilot and did his own flying.)

Eventually Peter does update Maggie on the invalid marriage and later decides she is the only girl for him. They marry. Sandra soon announces that she is pregnant with Peter’s child and vows to Maggie, “I’m going to get him back.” Her fangs are out—and not for the first or last time.

Eventually Peter does update Maggie on the invalid marriage and later decides she is the only girl for him. They marry. Sandra soon announces that she is pregnant with Peter’s child and vows to Maggie, “I’m going to get him back.” Her fangs are out—and not for the first or last time.

Peter leaves on a business trip and his plane promptly disappears in the Brazilian rain forest. He’s given up for lost.

Sandra admits she doesn’t want the coming baby. Maggie does—it’s the one thing she has left of Pete’s—and she proposes a deal. First, the two will call a truce. Second, she will guarantee the temperamental pianist financial security in exchange for the baby she will pass off as her own. Before Sandra’s pregnancy becomes noticeable, the two women rent an isolated cabin in an Arizona prairie where they await the baby’s arrival—with the unappreciated guidance of Maggie, who tries to persuade her charge to eat properly and stop drinking.

After the birth, Maggie returns to civilization, now a mother, and Sandra resumes her concert career. A year or so later Maggie receives a phone call. It’s Pete! Probably not much of a surprise. He’s been found alive and is coming home, landing outside the kitchen window before the day is over.

Maggie, Peter and the baby settle into domestic bliss, until—oops! Not heard from since that women’s agreement, Sandra drops in uninvited at the farm. She wants the baby and forces Maggie to tell Peter the truth. Peter is surprised, of course, but he gentlemanly concedes that Sandra has the right and consoles Maggie that they still have each other. Huh! Sandra thinks. She sits down at the nearby piano, plays a little Chopin and announces she’ll leave in the morning. The couple can keep the baby. If she can’t have Peter, she certainly doesn’t want Pete, Jr.!

Maggie, Peter and the baby settle into domestic bliss, until—oops! Not heard from since that women’s agreement, Sandra drops in uninvited at the farm. She wants the baby and forces Maggie to tell Peter the truth. Peter is surprised, of course, but he gentlemanly concedes that Sandra has the right and consoles Maggie that they still have each other. Huh! Sandra thinks. She sits down at the nearby piano, plays a little Chopin and announces she’ll leave in the morning. The couple can keep the baby. If she can’t have Peter, she certainly doesn’t want Pete, Jr.!

The best part of all this silliness is the extended episode in the Western cabin, no doubt the clincher for Astor’s Best Supporting Actress Oscar. She is alternately bitchy, vindictive, hysterical, full of that self-loathing mentioned earlier and, above all it seems, resentful of the patient, benevolent Maggie. There aren’t many original lines to be dredged up from the mucky murk of The Great Lie, but Astor delivers perhaps the best one in the film: “I’m not one of your anemic creatures who can get nourishment from a lettuce leaf. I’m a musician. I’m an artist. . . . I like food.”

As for Davis, she looks perky and schoolgirlish, with shoulder-length hair whose length varies from scene to scene, much as she looks in The Bride Came C.O.D., which began production some two weeks after filming ended on The Great Lie. (Davis married her second husband, Arthur Farnsworth, in the interim.) She and Brent are very natural together—it was their tenth film together—and no surprise, as she has said, “I had an all-time crush on George . . . to no avail.”

Davis is a bit more subdued than usual, maybe in contrast with Astor’s tour de force performance. Their screen squabbles, however, are antithetical to their off-screen alliance. On Davis’ urging, the two toiled to rewrite the weak script. The two ladies were so busy changing things that director Edmund Goulding would jokingly ask what they wanted him to do next. They still failed to make the concoction totally convincing, overlooking as well one flaw: during Maggie’s midwifing she never gives the lost Peter a thought or mention, yet when she returns to New York, she abruptly remembers him and becomes depressed.

Davis is a bit more subdued than usual, maybe in contrast with Astor’s tour de force performance. Their screen squabbles, however, are antithetical to their off-screen alliance. On Davis’ urging, the two toiled to rewrite the weak script. The two ladies were so busy changing things that director Edmund Goulding would jokingly ask what they wanted him to do next. They still failed to make the concoction totally convincing, overlooking as well one flaw: during Maggie’s midwifing she never gives the lost Peter a thought or mention, yet when she returns to New York, she abruptly remembers him and becomes depressed.

Davis’ career always had its ups and downs—outstanding films adjacent weak, sometimes terrible ones. But her undisputed peak came in the last two years of the ’30s, the first three of the ’40s, which produced Jezebel, Dark Victory, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, The Old Maid, The Letter, The Little Foxes and Now, Voyager. Few actresses, perhaps not even Katharine Hepburn, can boast such a tight succession of noteworthy films, concentrated in so brief a time.

The cast of The Great Lie includes some familiar supporting players: Grant Mitchell, the imposed upon home owner in The Man Who Came to Dinner, and Jerome Cowan, who, along with Astor, made The Maltese Falcon the same year. Perhaps Astor should have been Oscar nominated for Best Actress for that role—instead of Greer Garson for Blossoms in the Dust?—although Davis was nominated for The Little Foxes. ([intlink id=”288″ type=”category”]Joan Fontaine[/intlink] won for Suspicion.) Along with Mitchell and Cowan, Lucile Watson, Russell Hicks and Thurston Hall are wasted in throw away minor roles and Sam McDaniel, brother of Hattie, is the stock black domestic.

The score is by Davis’ favorite composer Max Steiner, who here is subservient to the classical source music. The main title is taken up with the opening of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat Minor, with hands moving up the keyboard in those three crashing chords. At most opportunities, Steiner interpolates the Tchaikovsky into the background score, although not to the extent that he would do with Herman Hupfeld’s “As Time Goes By” in Casablanca. Overheard backstage is Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Peter listens to a phonograph recording of Sandra’s latest release, Anton Rubinstein’s Piano Concerto No. 4 in D Minor.

The score is by Davis’ favorite composer Max Steiner, who here is subservient to the classical source music. The main title is taken up with the opening of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat Minor, with hands moving up the keyboard in those three crashing chords. At most opportunities, Steiner interpolates the Tchaikovsky into the background score, although not to the extent that he would do with Herman Hupfeld’s “As Time Goes By” in Casablanca. Overheard backstage is Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Peter listens to a phonograph recording of Sandra’s latest release, Anton Rubinstein’s Piano Concerto No. 4 in D Minor.

Although Astor was a trained pianist and did mimic perfectly the fingering, Max Rabinovitch did the actual playing off-camera and Norma Boleslavsky’s hands are seen in close-ups. Whenever Sandra plays the piano, it’s usually the Tchaikovsky, suggestive of a limited, one-piece pianist. If in a relaxed mood—to her that would be moderately high-strung—she indulges a little Chopin. In her Oscar acceptance speech, Astor thanked both Davis and Tchaikovsky.

Finally, although The Great Lie was pre-civil rights, one cannot help but be struck by the inappropriateness of the ethnic treatments. Hattie McDaniel, as a maid and cook, does another, perhaps slightly higher class version of Mammy in Gone With the Wind. She is given such lines as, “You ain’t gonna feed that man is you?” At one point, the black servants sing and dance, just as in those stereotypical plantation days. Maybe pre-civil rights, but the year is, after all, 1941. This is all a little off-putting and must discourage many viewers from listing the film among their favorites.

Finally, although The Great Lie was pre-civil rights, one cannot help but be struck by the inappropriateness of the ethnic treatments. Hattie McDaniel, as a maid and cook, does another, perhaps slightly higher class version of Mammy in Gone With the Wind. She is given such lines as, “You ain’t gonna feed that man is you?” At one point, the black servants sing and dance, just as in those stereotypical plantation days. Maybe pre-civil rights, but the year is, after all, 1941. This is all a little off-putting and must discourage many viewers from listing the film among their favorites.