A Personal Remembrance

A little walk down Memory Lane. So many of our fondest memories are tied to the movies, sometimes in life-changing ways. No deep analyses to follow, no revelations about profound movie-making, no study of great directors. I’ll put aside, for the moment, the masterful Twelve O’Clock High, the surrealistic score for Mysterious Island, the milestone Captain Blood and the frighteningly realistic Seven Days in May—types of films I’ve recently discussed—and take that walk. A change of pace for me, to be sure. So—care to join me? . . .

The movies which easily fit within these presumed restrictions, under the guise of relaxed escapism, are the four Agatha Christie mysteries British/M-G-M made in the mid-’60s, starring the elderly, rotund Margaret Rutherford, then in her early seventies. I first saw the films at the base theaters—each on separate occasions, of course!—as their releases coincided with my four years in the United States Air Force. Each time a new film was released, I could look around and be assured I was at a new base. Five during those years. And, appropriately enough, a year of that service was spent in England.

As music is instinctively paramount, not only in my life in general but, certainly, in appraising a movie, a responsibility which so many reviewers ignore, my first positive impression of these films was just that, Ron Goodwin’s score. It’s captivating, tuneful and always mirroring the screen, now for stalking, now for dark villainy, now for humor.

As music is instinctively paramount, not only in my life in general but, certainly, in appraising a movie, a responsibility which so many reviewers ignore, my first positive impression of these films was just that, Ron Goodwin’s score. It’s captivating, tuneful and always mirroring the screen, now for stalking, now for dark villainy, now for humor.

And, true, Ron was ever ready to “Mickey Mouse”—not a negative here. The “mousing” was, after all, part of the fun—mimicking a shiver of Rutherford’s ample jowls, a stinger chord to accompany “This man is dead!,” Inspector Craddock’s latest Marple frustration, a gloved hand turning on the gas. In more than one of these films, the music accompanies Miss Marple and Mr. Stringer jaunting down an English village street, whether to collect for the Reformed Criminals Assistance League or to find a murderer. The music changes in mood, in flashes, as the screen action requires—not announcing terror, for that, like “horror,” is too strong a word here, but exaggerating an already sensed impression that all is in good fun, even tongue in cheek. The music is about as subtle, sometimes, as that for a Tom and Jerry cartoon.

The Cast of Characters

But wait! More about the music later. Strangers to these films might ask, Who are Miss Marple, Inspector Craddock and Mr. Stringer? (These characters, and the actors who play them, are regulars in all four movies.) Good question. Miss Marple (Rutherford) is the Christie-created amateur sleuth, whose male counterpart in the author’s mystery pantheon is Hercule Poirot, who, if I remember correctly, met the old lady at least once among those fictional pages. Poirot, eccentric to the point of annoyance, inhabits the play worlds of the rich and the sophisticated. Miss Marple—Jane her first name—is the opposite: simple, down to earth; she moves, most often, in the domestic atmosphere of the supposed “quiet” English countryside. About which, you might remember, Sherlock Holmes himself made a rather unsettling remark: “ . . . the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside . . . ” Remember?

But wait! More about the music later. Strangers to these films might ask, Who are Miss Marple, Inspector Craddock and Mr. Stringer? (These characters, and the actors who play them, are regulars in all four movies.) Good question. Miss Marple (Rutherford) is the Christie-created amateur sleuth, whose male counterpart in the author’s mystery pantheon is Hercule Poirot, who, if I remember correctly, met the old lady at least once among those fictional pages. Poirot, eccentric to the point of annoyance, inhabits the play worlds of the rich and the sophisticated. Miss Marple—Jane her first name—is the opposite: simple, down to earth; she moves, most often, in the domestic atmosphere of the supposed “quiet” English countryside. About which, you might remember, Sherlock Holmes himself made a rather unsettling remark: “ . . . the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside . . . ” Remember?

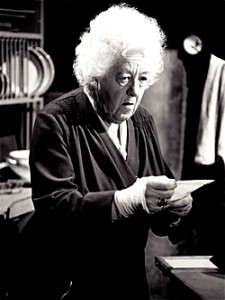

Margaret Rutherford as Miss Marple has an inexplicable, illogical command of the screen, with her jerky body motions, decidedly unShakespearean delivery and fleshy facial contortions. A dozen grimaces. There’s the tilt of her head, the roll of her tongue inside her mouth (most expertly behind her lower lip and traversing her left cheek), the pucker of her lips, the flex of her chin, the squint of an eye. Somewhat like the Robert Newton of female stars. Both have been called hams. Well, maybe. But these larger-than-life personalities hold your attention, often denying it to other players.

Margaret Rutherford as Miss Marple has an inexplicable, illogical command of the screen, with her jerky body motions, decidedly unShakespearean delivery and fleshy facial contortions. A dozen grimaces. There’s the tilt of her head, the roll of her tongue inside her mouth (most expertly behind her lower lip and traversing her left cheek), the pucker of her lips, the flex of her chin, the squint of an eye. Somewhat like the Robert Newton of female stars. Both have been called hams. Well, maybe. But these larger-than-life personalities hold your attention, often denying it to other players.

Inspector Craddock (Charles Tingwell) is here the stand-in for the bureaucrat, usually slow on the uptake, though likable and deserving audience sympathy for all policemen who bear the burden of the amateur detective. Craddock’s anxiety is particularly vexing, as Miss Marple often turns up unexpectedly where bodies lie about. “Good lord—it’s you!” he moans. Simultaneously surprised and not surprised, he utters this or any number of other variants with a shake of his head. That she is always right perplexes and irritates him. Although in one case she did pick the wrong murderer, but only for a moment. Craddock, in bewildered, sometimes silent expletives, does his part, maybe not intentionally, toward comic relief.

Inspector Craddock (Charles Tingwell) is here the stand-in for the bureaucrat, usually slow on the uptake, though likable and deserving audience sympathy for all policemen who bear the burden of the amateur detective. Craddock’s anxiety is particularly vexing, as Miss Marple often turns up unexpectedly where bodies lie about. “Good lord—it’s you!” he moans. Simultaneously surprised and not surprised, he utters this or any number of other variants with a shake of his head. That she is always right perplexes and irritates him. Although in one case she did pick the wrong murderer, but only for a moment. Craddock, in bewildered, sometimes silent expletives, does his part, maybe not intentionally, toward comic relief.

A quite different form of comic relief comes from Jim Stringer (Stringer Davis, Rutherford’s husband in real life). He fills the role of the sleuth’s proverbial friend, personified most famously in the personage of Sherlock Holmes’ Dr. Watson. If fortunately lacking Dr. Watson’s touches of buffoonery—at least in the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce films—Mr. Stringer, like Watson, manages to remain a few steps behind his master detective in comprehending the goings-on. Such puzzlements as “I’m afraid I’m at a loss, Miss Marple” or “You’re ahead of me there, Miss Marple” are frequent. Naturally, the old lady has to explain things to him—and to the audience. On one occasion, when she asks him, “Well, you do see the significance of this?,” he replies, “Ah—no.” Need more be said?—

A quite different form of comic relief comes from Jim Stringer (Stringer Davis, Rutherford’s husband in real life). He fills the role of the sleuth’s proverbial friend, personified most famously in the personage of Sherlock Holmes’ Dr. Watson. If fortunately lacking Dr. Watson’s touches of buffoonery—at least in the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce films—Mr. Stringer, like Watson, manages to remain a few steps behind his master detective in comprehending the goings-on. Such puzzlements as “I’m afraid I’m at a loss, Miss Marple” or “You’re ahead of me there, Miss Marple” are frequent. Naturally, the old lady has to explain things to him—and to the audience. On one occasion, when she asks him, “Well, you do see the significance of this?,” he replies, “Ah—no.” Need more be said?—

George Pollock, who died in 1979, is the journeyman director throughout the series.

The Agatha Christie Sources

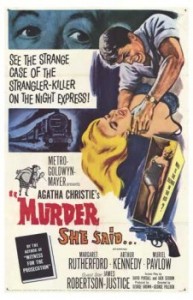

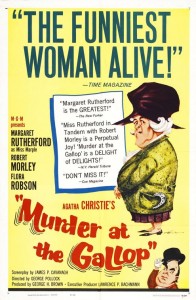

Murder, She Said, the first and perhaps finest of the quartet of films, is the only one based on an actual Miss Marple mystery—What Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw!, existing, as so often with Christie, in an alternate title, 4:50 from Paddington. The Poirot mysteries provide the source for two of the films: Murder at the Gallop, published variously as Funerals Are Fatal and After the Funeral, and Murder Most Foul, based on Mrs. McGinty’s Death, alias Blood Will Tell. Not Christie-based, Murder Ahoy was created by a pair of screen writers, David Pursall and Jack Seddon, who had worked on some of the previous films.

These movies were marketed as art films in the U.S. and became hits with the critics, but by the making of the fourth film, the public’s interest was “d-w-i-n-d-l-i-n-g—,” as Poirot said to Ratchett in the 1974 film version of Murder on the Orient Express. So a fifth installment, based on another Miss Marple whodunit, The Body in the Library, was never filmed.

These movies were marketed as art films in the U.S. and became hits with the critics, but by the making of the fourth film, the public’s interest was “d-w-i-n-d-l-i-n-g—,” as Poirot said to Ratchett in the 1974 film version of Murder on the Orient Express. So a fifth installment, based on another Miss Marple whodunit, The Body in the Library, was never filmed.

To watch the films is to realize that they are, after all, little jewels in their way, quite well made, with care and affection by all involved. The black and white photography is superb, the use of wide screen imaginative at times. The films weren’t quaint in the ’60s; that was an entirely different, less sophisticated age when audiences could be entertained by simple stories and simple plots, and ordinary characters could be endearing. Old people, even, could have major roles, though even these films were something of exceptions in that regard.

Hard to believe that movie-goers in the ’60s could actually be entertained by a dotty old actress and by such droll humor, cliché suspense gimmicks and the total absence of—can you believe it?!—explosions, car chases, gratuitous sex, violence and foul language. Those poor, deprived souls of that time! (If familiar with my byline, you have sensed this is one reason I prefer the old films.) Quaint though the films might be by today’s standards, it’s their naïveté that endears them to many viewers—and might endear even more now. During the ’30s, both Busby Berkeley musicals and the gangster flicks, quite different genres, diverted the minds of growing audiences from the Great Depression. Now, in the current hard times, I suggest these films would be ideal and for the same reason—good old-fashioned escapism.

And with the loss of the innocence of these films has come, now, another loss: much of what’s on screen—the villages, the manor houses, the landscapes—has vastly changed since I was stationed in England. Some sights, in fact, have disappeared entirely, as has much of picturesque old England.

And with the loss of the innocence of these films has come, now, another loss: much of what’s on screen—the villages, the manor houses, the landscapes—has vastly changed since I was stationed in England. Some sights, in fact, have disappeared entirely, as has much of picturesque old England.

If there’s a clear weakness in the mysteries, it’s the scenes of bickering and innuendo among the suspects, as they inevitably gather at dinner or in a drawing room for displays of suspicion, avarice and intimidation. “What about you, or can your secretary verify all your movements on that day?” “It’s not settled as far as I’m concerned!” “We’ll just have to keep the cupboard doors closed a little longer—stop the skeletons from rattling and all that.” The writers struggle, usually unsuccessfully, to make these scenes as interesting as Rutherford’s moments on screen.

Plot Summaries

Okay, at the outset I said any in-depth studies were unnecessary. But put differently, an awareness, let’s say, of the plots reveals certain recurring situations—experiments in Miss Marple’s laboratory (all right, her kitchen), Mr. Stringer forever traipsing to London or making inquiring phone calls, the murderers depending upon mystery novels for their ideas and the setting of traps for the criminals, Miss Marple’s alternative to Poirot’s extended dénouements.

In She Said, Miss Marple witnesses a strangulation on a passing train. She assumes the disguise of a domestic to investigate the goings-on at Ackenthorpe Hall (originally Crackenthorpe Hall), where she believes is hidden the victim’s body and where are gathered the usual array of Christie suspects. Typically, as here, the murderer is the person you’d never suspect—but should. As often in these films, Miss Marple boasts of winning some award, in this case the Ladies’ Golf Handicap of 1921. She hits golf balls to places she wishes to investigate.

In She Said, Miss Marple witnesses a strangulation on a passing train. She assumes the disguise of a domestic to investigate the goings-on at Ackenthorpe Hall (originally Crackenthorpe Hall), where she believes is hidden the victim’s body and where are gathered the usual array of Christie suspects. Typically, as here, the murderer is the person you’d never suspect—but should. As often in these films, Miss Marple boasts of winning some award, in this case the Ladies’ Golf Handicap of 1921. She hits golf balls to places she wishes to investigate.

In Gallop, she believes Mr. Enderby was frightened to death by a cat, his being deathly afraid of them. To an skeptical Inspector Craddock, she suggests that Christie’s The Ninth Life should be required reading by the police force, to discover, she says, “how doom came to her victim in the shape of a cat.” She joins a riding academy to snoop and, yes, encounters five or six suspects. But once again—maybe you’ve caught on already—the murderer is someone you wouldn’t suspect, someone always “out and about,” a nonentity affecting shyness—“shy,” the very word Miss Marple used in first describing the individual. Here Miss Marple boasts of having garnered an equestrian trophy in 1910.

In Gallop, she believes Mr. Enderby was frightened to death by a cat, his being deathly afraid of them. To an skeptical Inspector Craddock, she suggests that Christie’s The Ninth Life should be required reading by the police force, to discover, she says, “how doom came to her victim in the shape of a cat.” She joins a riding academy to snoop and, yes, encounters five or six suspects. But once again—maybe you’ve caught on already—the murderer is someone you wouldn’t suspect, someone always “out and about,” a nonentity affecting shyness—“shy,” the very word Miss Marple used in first describing the individual. Here Miss Marple boasts of having garnered an equestrian trophy in 1910.

In Foul, our sleuth is the only one of twelve jurors who believes the defendant didn’t kill Mrs. McGinty, so—off she goes, becoming part of a theatrical troupe where she suspects the real killer is blackmailing one of its players. “In a trap set for me,” she tells Inspector Craddock, “poor Dorothy died. The iron was hot, you see.” “No, I don’t see,” he responds. “Well,” she assures him, “tonight I have returned the compliment.” At the climax, her expertise with a hand gun comes to the fore, as, of course—she did win the Ladies’ Small Arms Championship in Bisley in 1924. Unfortunately, Inspector Craddock falls foul (pun intended) of the lady’s marksmanship, but he survives, promoted to chief inspector.

In Foul, our sleuth is the only one of twelve jurors who believes the defendant didn’t kill Mrs. McGinty, so—off she goes, becoming part of a theatrical troupe where she suspects the real killer is blackmailing one of its players. “In a trap set for me,” she tells Inspector Craddock, “poor Dorothy died. The iron was hot, you see.” “No, I don’t see,” he responds. “Well,” she assures him, “tonight I have returned the compliment.” At the climax, her expertise with a hand gun comes to the fore, as, of course—she did win the Ladies’ Small Arms Championship in Bisley in 1924. Unfortunately, Inspector Craddock falls foul (pun intended) of the lady’s marksmanship, but he survives, promoted to chief inspector.

When, in Ahoy, a man dies from poisoned snuff, Miss Marple visits the officers on an old training ship, the “Battledore.” Lionel Jeffries somewhat steals the show with his eccentric, often over-the-top Captain Rhumstone. An exchange of Morse code flashlight signals—Miss Marple in the great cabin of the ship, Mr. Stringer ashore—is a delightful moment, with Goodwin’s “twinkling” music synchronized with the flashes. The expected trap this time draws out a killer who engages Miss Marple in a sword fight. Even though she was, of course, the Ladies’ National Fencing Champion of 1931, she’s not quite up to snuff (another pun?). Mr. Stringer saves her in the nick of time! Did I say “nick”?

When, in Ahoy, a man dies from poisoned snuff, Miss Marple visits the officers on an old training ship, the “Battledore.” Lionel Jeffries somewhat steals the show with his eccentric, often over-the-top Captain Rhumstone. An exchange of Morse code flashlight signals—Miss Marple in the great cabin of the ship, Mr. Stringer ashore—is a delightful moment, with Goodwin’s “twinkling” music synchronized with the flashes. The expected trap this time draws out a killer who engages Miss Marple in a sword fight. Even though she was, of course, the Ladies’ National Fencing Champion of 1931, she’s not quite up to snuff (another pun?). Mr. Stringer saves her in the nick of time! Did I say “nick”?

Mystery novels themselves—all fictitious, as best I can determine—play parts in three of the films. In She Said, Falcon Smith’s The Hatrack Hanging, which Mr. Stringer has been reserving for Miss Marple, provides a comic moment in the public library where he works. She cajoles from him assurance that their having read hundreds of detective novels qualifies them as detectives. . . . In Gallop, there is that reference to the “Christie” The Ninth Life, which presumably Agatha never penned. . . . In Ahoy, The Doom Box, by Jane Plantagenet Corby (need a good pseudonym?), describing snuff as a method of dispatch, just happens to be in the old lady’s library. She reaches the book via some movable steps, which Mr. Stringer maneuvers. “Propel me, please, Jim.” . . . In Foul, in place of mystery novels, there’re references to plays: Remember September and The Lodger’s Dilemma. From Out of the Stewpot, the killer purloins the scheme in which a sauce pan of poison is turned on, to melt and evaporate, then turned off by the stove timer. Miss Marple, of course, demonstrates.

The Supporting Casts

In addition to the three regular actors, there’re the secondary stars of the day and guest appearances: in She Said, Arthur Kennedy and James Robinson Justice; in Gallop, Robert Morley and Flora Robson; in Foul, Ron Moody and, in a minor part toward the end, Dennis Price (best remembered for Kind Hearts and Coronets); and in Ahoy, Lionel Jeffries. Of these, two are the designated murderers. Shh-h-h—— Scattered throughout, in less prominent roles, are other familiar contemporary faces, resembling, though hardly equaling, the supporting players of the ’30s and ’40s. In She Said, Ronald Howard, son of Leslie Howard, plays one of the nondescript suspects. Related to this genre, Howard made something like thirty-nine, 30-minute TV episodes playing Sherlock Holmes in a French-made series, 1954-55. Joan Hickson, who later became her own Miss Marple incarnation in a BBC series, plays a disgruntled maid. “One of the younger generation,” Miss Marple bemoans (Hickson was 55!). Also present is long-forgotten Ronnie Raymond, playing a snotty, pseudo-intelligent, yet likable kid. “Better get your alibis ready,” he warns the family, gathered, not surprisingly, for dinner. Raymond steals scenes from everyone, including Rutherford.

In addition to the three regular actors, there’re the secondary stars of the day and guest appearances: in She Said, Arthur Kennedy and James Robinson Justice; in Gallop, Robert Morley and Flora Robson; in Foul, Ron Moody and, in a minor part toward the end, Dennis Price (best remembered for Kind Hearts and Coronets); and in Ahoy, Lionel Jeffries. Of these, two are the designated murderers. Shh-h-h—— Scattered throughout, in less prominent roles, are other familiar contemporary faces, resembling, though hardly equaling, the supporting players of the ’30s and ’40s. In She Said, Ronald Howard, son of Leslie Howard, plays one of the nondescript suspects. Related to this genre, Howard made something like thirty-nine, 30-minute TV episodes playing Sherlock Holmes in a French-made series, 1954-55. Joan Hickson, who later became her own Miss Marple incarnation in a BBC series, plays a disgruntled maid. “One of the younger generation,” Miss Marple bemoans (Hickson was 55!). Also present is long-forgotten Ronnie Raymond, playing a snotty, pseudo-intelligent, yet likable kid. “Better get your alibis ready,” he warns the family, gathered, not surprisingly, for dinner. Raymond steals scenes from everyone, including Rutherford.

In Gallop, Duncan Lamont, as a red herring stable hand, is perhaps best remembered, if at all, for roles in Arabesque (1966), Battle of Britain (1969) and a personal favorite, A Touch of Larceny (1959). Finlay Currie’s entire “role” consists of clutching his chest and falling down a flight of stairs. From among his over 130 movies, two signal characters are Magwitch in David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) and Saint Peter in Quo Vadis? (1951).

In Gallop, Duncan Lamont, as a red herring stable hand, is perhaps best remembered, if at all, for roles in Arabesque (1966), Battle of Britain (1969) and a personal favorite, A Touch of Larceny (1959). Finlay Currie’s entire “role” consists of clutching his chest and falling down a flight of stairs. From among his over 130 movies, two signal characters are Magwitch in David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) and Saint Peter in Quo Vadis? (1951).

In Foul, Andrew Cruickshank appears near the beginning as a bored judge and is never seen again, though seen many, many times as Dr. Cameron in the British series Dr. Finlay’s Casebook, running 1962-71.

In Ahoy, appearing as a bishop in the opening scene, Miles Malleson, like Rutherford, is ample of jowl. He may be more familiar as the overly solicitous Mr. Fortesque in Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright or as still another bishop, an avid spider-collector, in the 1959 Hound of the Baskervilles, with Peter Cushing.

Delving into the subsequent careers of many of these character stars is personally fascinating, though here I limit my effusive instinct to a single case in point. Muriel Pavlow, a British actress to the core (and still alive at this writing), plays Emma Ackenthorpe in She Said. (With her demure screen persona, you never once imagine her to be the murderer, which she isn’t.) As recently as 1996, she still had her foot in the mystery door, as it were, appearing in, of all things, one of the Poirot/BBC whodunits. In “Dumb Witness,” David Suchet, perhaps the best Poirot characterization, gleans “testimony” from—are you ready?—a fox terrier named Bob. No, seriously. . . . No, seriously!

Delving into the subsequent careers of many of these character stars is personally fascinating, though here I limit my effusive instinct to a single case in point. Muriel Pavlow, a British actress to the core (and still alive at this writing), plays Emma Ackenthorpe in She Said. (With her demure screen persona, you never once imagine her to be the murderer, which she isn’t.) As recently as 1996, she still had her foot in the mystery door, as it were, appearing in, of all things, one of the Poirot/BBC whodunits. In “Dumb Witness,” David Suchet, perhaps the best Poirot characterization, gleans “testimony” from—are you ready?—a fox terrier named Bob. No, seriously. . . . No, seriously!

Ron Goodwin’s Music

Now back to the music! As Dimitri Tiomkin is most memorably associated with Westerns, Max Steiner with Bette Davis melodramas and Erich Wolfgang Korngold with the swashbucklers of Errol Flynn, so Ron Goodwin is the unofficial “war composer,” primarily World War II, i.e., Battle of Britain, Where Eagles Dare, Operation Crossbow, 633 Squadron, Submarine X-1, Force Ten from Navarone, among others. Goodwin died in 2003.

Now back to the music! As Dimitri Tiomkin is most memorably associated with Westerns, Max Steiner with Bette Davis melodramas and Erich Wolfgang Korngold with the swashbucklers of Errol Flynn, so Ron Goodwin is the unofficial “war composer,” primarily World War II, i.e., Battle of Britain, Where Eagles Dare, Operation Crossbow, 633 Squadron, Submarine X-1, Force Ten from Navarone, among others. Goodwin died in 2003.

In the Rutherford mysteries, a prominent harpsichord is central to the music, with much for the strings to do, sometimes becoming a pizzicato concert all their own. Quite anachronistic to this, but topical for the ’60s, is the rock ’n’ roll rhythms, offsetting the baroque tinges but generally absent from most of the score. Miss Marple attends a dance in Gallop and shimmies to the beat of the day. In Foul, when a cat appears from a cupboard, Goodwin, in something of an “in” joke, quotes the “Cat’s Theme” from Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, although the tune is generally lost beneath the noise of the soundtrack.

An excellent, spaciously recorded sampling of Goodwin’s music is available on a relatively recent Chandos CD, though it contains only a snippet of what is identified as “Miss Marple Theme.” It’s actually the Murder Ahoy main title, complete with allusions to sea shanties, particularly “A-Roving.” Ron Shillingford wrote the generally excellent liner notes without, unfortunately, revealing much technical information about the scores. Tantalizingly, he explains that Goodwin actually assembled a 22-minute Miss Marple Suite, which was recorded in 1992.

Let’s close this little walk down Memory Lane with a humorous story, which not only complements these films but confirms the old adage that directors and producers rarely know anything about music (perhaps the basis for another volume?) Shillingford relates that, in scoring The Trap (1966)—not a war movie but about a fur trapper taking a mute wife—Goodwin sent producer George Brown a demo of his main theme, this before the days of computers. Brown said he didn’t feel the music right for the movie. Goodwin, however, thought it perfectly fine and decided to use it, unaltered. Brown, who was present at the recording session, said, “Well, Ron, that’s much better than the tune you sent me”!