“Harry, do you know what you’re doing? You’re killing me. You’re killing me and yourself.” — Mary Bristol to Harry Fabian

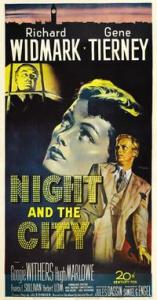

iNght and the City is the darkest, the most unrelenting film noir, full of despicable characters for whom no one has any sympathy and so oppressively film noir, that had it not come so late in the genre’s history—1950—film scholars would delight in declaring it the prototype. It is certainly one of the best, even though, after watching it, you may feel a bit depressed, somewhat disappointed in people, even a little—well, dirty.

As in numerous successful, even great movies, many talents went into making Night and the City what it is. Jo Eisinger’s script, taunt and harsh in the extreme, though, strangely, with few memorable lines, is based on Gerald Kersh’s 1946 novel. Jules Dassin’s direction, however, is oddly snappy despite the weight the screen and plot are forced to support. Perhaps more familiar to movie goers for Never on Sunday and Topkapi, he is a master of crime and film noir, though inexplicably omitted from most lists of the greats—Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder and Anatole Litvak. Just previous to Night and the City he had directed three other noirs: Brute Force, The Naked City and Thieves’ Highway.

Hardly of less importance, perhaps the first thing an audience notices here, is Max Greene’s (nè Mutz Greenbaum) unusually dark, shadowy cinematography, with many close-ups, shots from the floor and tight photography in general. C.P. Norman’s matching art direction is another instance of like minds working together. The screen is so full of cage-like shapes, confining iron staircases, grates, wire partitions, solid walls and stairs that lead to locked doors that the audience immediately feels the claustrophobic, confining “prison” of these characters’ lives. They all appear enmeshed in some gigantic, metaphoric spider web, unable to escape either the web or each other. Sadly, it seems that these denizens of the dark, most of them criminals to various degrees, belong locked in such confinements.

Hardly of less importance, perhaps the first thing an audience notices here, is Max Greene’s (nè Mutz Greenbaum) unusually dark, shadowy cinematography, with many close-ups, shots from the floor and tight photography in general. C.P. Norman’s matching art direction is another instance of like minds working together. The screen is so full of cage-like shapes, confining iron staircases, grates, wire partitions, solid walls and stairs that lead to locked doors that the audience immediately feels the claustrophobic, confining “prison” of these characters’ lives. They all appear enmeshed in some gigantic, metaphoric spider web, unable to escape either the web or each other. Sadly, it seems that these denizens of the dark, most of them criminals to various degrees, belong locked in such confinements.

The score provides an equally important ingredient, adding its own dark, harsh, angular, unhappy nuance, though never subtly. Nothing subtle about this movie. Herein, however, lies some confusion, owing, perhaps, to the film’s British origins. Night and the City has two different scores. The British version is by Benjamin Frankel (Battle of the Bulge, The Night of the Iguana), the America version by Franz Waxman (Sunset Blvd., The Bride of Frankenstein). Why I would be watching on American TV the British version—I was introduced to this film only recently—I don’t know, but, to me, the score I heard sounded more like Frankel, more thinly scored, more dissonant, more angular, more generally “modern” than I’m accustomed to in Waxman. Whichever score I heard, it was first rate.

The acting is uniformly good, even if you notice the acting, blended in, as it is, with all those other distracting, overpowering elements. The cast has something of an international touch, with Americans slightly ahead in three main roles, although two are small compared with Richard Widmark’s forceful presence. Some would be justified in thinking Gene Tierney and Hugh Marlowe are slighted in their minuscule parts; if anything, these two characters seem the closest to “normal” of any one here, although they, too, are entangled in the same web.

The acting is uniformly good, even if you notice the acting, blended in, as it is, with all those other distracting, overpowering elements. The cast has something of an international touch, with Americans slightly ahead in three main roles, although two are small compared with Richard Widmark’s forceful presence. Some would be justified in thinking Gene Tierney and Hugh Marlowe are slighted in their minuscule parts; if anything, these two characters seem the closest to “normal” of any one here, although they, too, are entangled in the same web.

To dwell for a moment, and justifiably, on Widmark, for this is his picture—— He doesn’t have to act, really, just be photographed! Night and the City was, remarkably, his fourth film noir—almost in a row, were it not for the sea saga Down to the Sea in Ships (1949), the actor here in a refreshing, non-neurotic role. His three earlier film noirs are The Street with No Name and Road House, both from 1948, and his movie début in Kiss of Death the year before. From this last is borrowed the sinister laugh that helps animate his eccentric part in Night and the City.

Of interest, perhaps is the one Western, Yellow Sky, Widmark made during this time. Sharing the film with the by then seasoned Gregory Peck, the film is unfortunately neglected; directed by none other than William Wellman, it has some of the dark atmosphere of the director’s earlier The Ox-Bow Incident.

Of interest, perhaps is the one Western, Yellow Sky, Widmark made during this time. Sharing the film with the by then seasoned Gregory Peck, the film is unfortunately neglected; directed by none other than William Wellman, it has some of the dark atmosphere of the director’s earlier The Ox-Bow Incident.

The major British contingent is headed by Googie Withers, the second woman of interest, and Francis L. Sullivan. While Withers is little known to American audiences, though possibly through Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (as Blanche), Sullivan is something of a Charles Dickens specialist. He stars as lawyer Jaggers in both the 1934 and the 1946 versions of Great Expectations, as the Reverend Crisparkle in The Mystery of Edwin Drood and as Mr. Bumble in Oliver Twist (1948). While Widmark is “up and at ’em,” over the top and loud, Sullivan is depressed and repressed in his role, all inward, and Widmark’s only real threat in the acting category.

The Czechs are represented by the versatile Herbert Lom—for those of us accustomed to him in the Pink Panther movies here looking awfully young, “only” thirty-three. With a face that combines Victor McLaglen’s and Nat Pendleton’s for ugliness, the Ukrainian Mike Mazurki has, like those actors, an enormous physical presence. Having playedgangsters all his career, he must have felt right at home in the milieu of Night and the City.

The Czechs are represented by the versatile Herbert Lom—for those of us accustomed to him in the Pink Panther movies here looking awfully young, “only” thirty-three. With a face that combines Victor McLaglen’s and Nat Pendleton’s for ugliness, the Ukrainian Mike Mazurki has, like those actors, an enormous physical presence. Having playedgangsters all his career, he must have felt right at home in the milieu of Night and the City.

The most brilliant bit of casting is the Polish-born Stanislaus Zbyszko as a Greco-Roman wrestler in the second of only two theatrical films he made. Also of great mass, he was an authentic U.S. champion heavyweight wrestler, between 1909 and the 1920s.

Look quickly among the ladies for an uncredited Kay Kendall, the English actress who, trained in ballet and is perhaps best known for Genevieve and Les Girls, was the second wife of Rex Harrison. When Harrison fell in love with her, he was married to Lilli Palmer. He divorced Palmer and married Kendall, never telling her she had leukemia, a pact of secrecy he had also made with her doctor. They had been married a little over two years when she died in 1959.

The setting of Night and the City is London in the late 1940s, just after World War II and, for residents, with still-vivid reminders of the Blitz in the lingering rubble and the horrid memories. In this great city not yet put back together, there is still heavy—if not heavier than before—rationing, and the accompanying black market. Both director and cinematographer immerse the screen in the atmosphere of a dark, torn London the way Carol Reed does in The Third Man, with another damaged, post-war metropolis, Vienna; the way Dassin does again in The Naked City with corruption in New York City; the way Hitchcock does in Frenzy, with the underside of a London twenty years later.

The setting of Night and the City is London in the late 1940s, just after World War II and, for residents, with still-vivid reminders of the Blitz in the lingering rubble and the horrid memories. In this great city not yet put back together, there is still heavy—if not heavier than before—rationing, and the accompanying black market. Both director and cinematographer immerse the screen in the atmosphere of a dark, torn London the way Carol Reed does in The Third Man, with another damaged, post-war metropolis, Vienna; the way Dassin does again in The Naked City with corruption in New York City; the way Hitchcock does in Frenzy, with the underside of a London twenty years later.

The central character in this ugly little story—no getting around it, either in presence or performance—is Harry Fabian (Widmark), a real lowlife and lost morally, a wanderer from joint to joint. Like many people, he wants “to be somebody,” as he says flat-out, and he thinks money is the way to achieve it. But when his unhappy lover Mary (Tierney) refuses to loan him any more money, he turns to Helen Nosseross (Withers) for solace—and money.

Helen has been turned off by her obese, amorous husband Phil (Sullivan), the oily owner of the Silver Fox nightclub. In leaving her husband, Helen is cruel, ignoring his desperate pleas for her to stay and blatantly assuring him that she won’t be back. Her future, she believes, is with Fabian, this wheeler-dealer of the underground. She goes along with his craving for an affair because, as she’s also a user of people, she plans to coax out of him a license to reopen a closed nightclub.

Helen has been turned off by her obese, amorous husband Phil (Sullivan), the oily owner of the Silver Fox nightclub. In leaving her husband, Helen is cruel, ignoring his desperate pleas for her to stay and blatantly assuring him that she won’t be back. Her future, she believes, is with Fabian, this wheeler-dealer of the underground. She goes along with his craving for an affair because, as she’s also a user of people, she plans to coax out of him a license to reopen a closed nightclub.

Old Phil discovers his wife’s affair and decides to lead Fabian down the proverbial garden path, first giving him a much-needed loan that he knows will turn Fabian’s projected success into a decided failure. Fabian, too, has an angle. With the money, he wants in on London’s pro-wrestling racket, and to get around the controlling kingpin, Kristo (Lom), he makes a deal with Kristo’s father, Gregorius (Zbyszko), a famous Greco-Roman wrestler. Fabian promises his conduct will be aboveboard—not like the crude style of Kristo’s star wrestler “The Strangler”(Mazurki).

There is a fight between Gregorius and “The Strangler.” Although it is in a ring as such, it’s not before an audience—and is an angry, to-the-death grudge fight between two enemies. It is well staged and terribly realistic in its scripting. At the time, it must have been almost too brutal to watch, and it remains a bit disturbing, even now. Gregorius wins, but dies a short time later in his son’s arms.

There is a fight between Gregorius and “The Strangler.” Although it is in a ring as such, it’s not before an audience—and is an angry, to-the-death grudge fight between two enemies. It is well staged and terribly realistic in its scripting. At the time, it must have been almost too brutal to watch, and it remains a bit disturbing, even now. Gregorius wins, but dies a short time later in his son’s arms.

In the meantime, Helen has discovered that the nightclub license Fabian has acquired for her is a forgery, and she—what else to do?—drags herself back to Phil. The scene is not the first of its kind, and the viewer can pretty much anticipate the surprise. Helen enters Phil’s office. He’s sitting at his desk, his back to her. There’s a cigarette smoldering in an ashtray. She speaks. He does not answer or turn his desk chair around. He is, of course, dead. Suicide. His love for her must have been stronger than her disgust for him.

Fabian is on borrowed time—Kristo, among others, is out to get him—and he flees through the backstreets of London, with its blitzed ruins, dark alleys, murky riverfronts and deserted factories. (Here the chaos and Fabian’s flight are represented by a wealth of tracking shots, close-ups, disturbing tilts and an unusual blackness.) Anna (Maureen Delaney), a black market contact, cannot offer him a hiding place and suggests he move on. Nor is there any help from Mary, who seeks him out on Hammersmith Bridge. Nor from Adam (Marlowe).

Fabian is on borrowed time—Kristo, among others, is out to get him—and he flees through the backstreets of London, with its blitzed ruins, dark alleys, murky riverfronts and deserted factories. (Here the chaos and Fabian’s flight are represented by a wealth of tracking shots, close-ups, disturbing tilts and an unusual blackness.) Anna (Maureen Delaney), a black market contact, cannot offer him a hiding place and suggests he move on. Nor is there any help from Mary, who seeks him out on Hammersmith Bridge. Nor from Adam (Marlowe).

Kristo appears in the distance, at the end of a long, highly chiaroscuroed cobblestone street. Fabian runs toward him, shouting that Mary betrayed him. “The Strangler” kills Fabian and throws his body into the Thames. So, in film noir fashion, everyone gets their comeuppance—if not dead, then in jail; if not jobless, then nearly so; if not disillusioned, then desperately unhappy.

Kristo appears in the distance, at the end of a long, highly chiaroscuroed cobblestone street. Fabian runs toward him, shouting that Mary betrayed him. “The Strangler” kills Fabian and throws his body into the Thames. So, in film noir fashion, everyone gets their comeuppance—if not dead, then in jail; if not jobless, then nearly so; if not disillusioned, then desperately unhappy.

Throughout the movie, the audience wants to like Harry . . . almost said “Lime” . . . wants to like Harry Fabian. Yet in no way, perhaps, is he really likable. He remains as unlikable as that fellow in The Third Man, though without either Lime’s erudition or his smattering of charm. It’s unfair, and untrue, that the viewer has to like, or even accept, Fabian or else the picture fails. Apart from Fabian, there are too many other compelling elements in Night and the City to have the film hang on one character, even if he happens to be the main character.

But Fabian has a way of begging, promising, cajoling people into doing him favors, and those same people—certainly new, naïve acquaintances—somehow believe he will deliver. His enthusiasm, and that he does seem to believe in himself, has to be admired, as does his striving to “become somebody” and not just the “some body” he eventually becomes in the end.

But Fabian has a way of begging, promising, cajoling people into doing him favors, and those same people—certainly new, naïve acquaintances—somehow believe he will deliver. His enthusiasm, and that he does seem to believe in himself, has to be admired, as does his striving to “become somebody” and not just the “some body” he eventually becomes in the end.