“You know something, Ann? No one I know of lies with such sincerity.” – John Malcolm (Burt Lancaster)

Perhaps, though, not too many people who were there, April 6, 1959, would like to remember the Oscar ceremonies honoring the films of 1958. It was a disaster. There were, of course, high moments—Susan Hayward finally received the Best Actress award (for I Want to Live!) after four previous unsuccessful nominations, a 70-year-old Maurice Chevalier was given an honorary award and Ingrid Bergman appeared on stage after a ten-year absence—but the evening erupted in chaos when the televised show ended twenty minutes short of its scheduled two hours. To fill the time, Jerry Lewis clowned and the confused on-stage stars danced extemporaneously, until NBC ended the agony with a pre-recorded sports video.

Perhaps, though, not too many people who were there, April 6, 1959, would like to remember the Oscar ceremonies honoring the films of 1958. It was a disaster. There were, of course, high moments—Susan Hayward finally received the Best Actress award (for I Want to Live!) after four previous unsuccessful nominations, a 70-year-old Maurice Chevalier was given an honorary award and Ingrid Bergman appeared on stage after a ten-year absence—but the evening erupted in chaos when the televised show ended twenty minutes short of its scheduled two hours. To fill the time, Jerry Lewis clowned and the confused on-stage stars danced extemporaneously, until NBC ended the agony with a pre-recorded sports video.

As for the films themselves, 1958 wasn’t an especially noteworthy year, about par for the decade. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof wasn’t among the better Tennessee Williams adaptations; not surprising, then, that none of its six nominations bore fruit. A better film, The Defiant Ones prospered, with nine nominations and two Oscars. Auntie Mame owed its watchability to star Rosalind Russell, nominated Best Actress unsuccessfully, as she had been in three previous years.

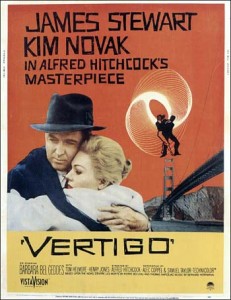

The actual best film of the year, and the most talked about since, wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture, nor was its director. As so often, a re-evaluative look-back at what Academy voters were thinking at the time produces utter bewilderment at their seduction by the froth of the Parisian musical Gigi (nine Oscars, including Best Picture) when Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo went unrecognized. It did receive nominations for art/set direction and sound, but, also surprising, the music, one of the great scores of Hollywood, was totally ignored, as the anti-Bernard Herrmann clique was still afoot. Benny offended Hollywoodians by haughtily distancing himself from them. Many critics and average movie-goers, both, regard Vertigo as Hitchcock’s masterpiece, though not this writer.

The actual best film of the year, and the most talked about since, wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture, nor was its director. As so often, a re-evaluative look-back at what Academy voters were thinking at the time produces utter bewilderment at their seduction by the froth of the Parisian musical Gigi (nine Oscars, including Best Picture) when Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo went unrecognized. It did receive nominations for art/set direction and sound, but, also surprising, the music, one of the great scores of Hollywood, was totally ignored, as the anti-Bernard Herrmann clique was still afoot. Benny offended Hollywoodians by haughtily distancing himself from them. Many critics and average movie-goers, both, regard Vertigo as Hitchcock’s masterpiece, though not this writer.

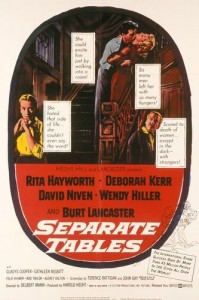

The fifth Best Picture nomination that year—last alphabetically—was Separate Tables. Like many films, its birth pangs were unsettling, and some remain visible—and audible—on screen. The first of the problems began before the cameras ever turned. Terence Rattigan’s two, one-act plays revolve around two couples, played by the same pair, who, of course, never appear in the same scenes together. Although Rattigan did his best to mesh his two plays into an harmonious whole for the film, in what now became four different actors, it took John Gay to find the solution—not the English poet and dramatist John Gay (1685-1745) but the California-born screenwriter (1924- ) who worked mostly in television.

Laurence Olivier and wife Vivien Leigh were considering the film as the original two major stars, with Olivier to direct, but backed out when they learned there would be four major stars in the play’s final transformation. Wendy Hiller, as the manager of the seaside British hotel, had thought her position in the fifth most substantial role was too small—until she got into the part and ended up winning the Supporting Actress Oscar.

Laurence Olivier and wife Vivien Leigh were considering the film as the original two major stars, with Olivier to direct, but backed out when they learned there would be four major stars in the play’s final transformation. Wendy Hiller, as the manager of the seaside British hotel, had thought her position in the fifth most substantial role was too small—until she got into the part and ended up winning the Supporting Actress Oscar.

Director Delbert Mann felt Burt Lancaster’s cutting of many of Deborah Kerr’s early scenes prior to his first appearance denied her a shoo-in as Best Actress, for which she was nominated. Lancaster’s company Hecht-Hill-Lancaster produced the film, and, as Mann theorized, the actor cut those scenes to move forward his entry in the film, as he was the last of the major stars to appear.

Even the film’s music didn’t emerge unscathed, and, on screen, ended up revised and mangled, much to the resentment of composer David Raksin. First, the frequent acidic tones, aptly reflecting the misery and distress of the characters and their relationships, were softened and, in several scenes between Lancaster and Rita Hayworth, romanticized, incongruous with their usual bickering.

Even the film’s music didn’t emerge unscathed, and, on screen, ended up revised and mangled, much to the resentment of composer David Raksin. First, the frequent acidic tones, aptly reflecting the misery and distress of the characters and their relationships, were softened and, in several scenes between Lancaster and Rita Hayworth, romanticized, incongruous with their usual bickering.

Second, and worst of all, a title song—this when title songs were practically mandatory—was added behind the opening credits: Vic Damone singing—what else?!—“Separate Tables” by Harry Warren and Harold Adamson. Raksin was told if he didn’t re-do the main title, now using someone else’s music, another composer would. Raksin reluctantly complied and, as a result, Mann severed his contract with Hecht-Hill-Lancaster. Since the music was nominated Best Score (for a dramatic or comedy picture), one wonders how Raksin’s acceptance speech would have gone had he won! The winner was Dimitri Tiomkin for The Old Man and the Sea.

An interesting and confusing footnote here: Despite the occasional reference to the title song being “written but not used in the final film,” it does, in fact, appear in some prints of Separate Tables, namely in the M-G-M DVD release, with, on the cover, Lancaster and Hayworth embraced on a staircase. There are, however, other prints which contain Raksin’s original main title, sans song, as in the version that Director Mann witnessed at a retrospective of supposed “British films.” Viewers are encouraged to seek out the latter.

In defense of that bygone way of making movies, Mann has said, “The older audience of my generation . . . across the country and across the world . . . have been driven out of the theaters by the foul language and the sex and the violence of all kinds, and I have close friends who grew up going to the movies couple times a week . . . [They] have not been into a motion picture house in ten years . . . The reliance, today, on special effects, large, booming sound, quick cutting, close shooting, close-up, close-up—it’s a different world . . . ”

Separate Tables is a quiet, dialogue-filled movie, its stage origins quite obvious and not the kind of film most present-day audiences would sit through, unfortunately. There are no explosions, no car chases, no nudity, not even a fist clenched in anger, though John Malcolm (Lancaster) and Ann Shankland (Hayworth) do cast glaring eyes at each other. Ann is a fading fashion model trying to hide her age and reclaim her alcoholic ex-husband, who is engaged to Pat Cooper (Hiller).

Separate Tables is a quiet, dialogue-filled movie, its stage origins quite obvious and not the kind of film most present-day audiences would sit through, unfortunately. There are no explosions, no car chases, no nudity, not even a fist clenched in anger, though John Malcolm (Lancaster) and Ann Shankland (Hayworth) do cast glaring eyes at each other. Ann is a fading fashion model trying to hide her age and reclaim her alcoholic ex-husband, who is engaged to Pat Cooper (Hiller).

In these residents of the Beauregard Hotel in Bournemouth astute observers will sense a study in loneliness. Even the film’s title suggests isolation, as each person sits at a separate table in the hotel’s dining room. In some ways, the loneliness is most poignantly illustrated in Mr. Fowler (Felix Alymer), the retired classics professor who anxiously awaits a visit from a former student who never comes. How much he is hurt and, also, how his perspective of life has narrowed are expressed in his comment after dinner: “What a pity young Reginald wasn’t here. He’d enjoyed the turnover. The cook’s acquiring a lighter touch in her pastry, don’t you think?”

The most lonely resident, shy and sexually repressed, is Sibyl Railton-Bell (Kerr), afraid to even say the word “sex.” She is reminded of her inadequacies and reproached for her familiarity with an equally repressed fellow resident by her domineering mother (Gladys Cooper). When Mrs. Railton-Bell reads in a local paper that Sibyl’s friend, Major Pollock (David Niven), has behaved lewdly in a local cinema, she deliberately sets out to hurt her daughter.

There is Miss Meacham (May Hallatt), who follows the horses, reads detective novels and has, perhaps if not the most dramatic lines in the film, certainly the most humorous: “And what do I know of morals and ethics? Only what I read in novels, and as I only read thrillers, that doesn’t amount to much. . . . Well, my views of Major Pollock are that he’s always been a crashing old bore and a wicked old fraud, and now I hear he’s a dirty old man, too, I’m not surprised. And, quite between these four walls, I don’t give a damn.”

Niven deservedly won the Best Actor award in 1958 for his role as Pollock, who regales his companions with embellished stories of his World War II exploits. Most viewers will immediately sense his duplicity. Before he’s spoken a word—in his “walk-on” introduction, in fact—he abruptly adopts an extroverted swagger and a different twirl of his walking stick. A young student, Charles (Rod Taylor), is also onto Pollock. When the major boasts of attending a couple of military schools, Charles asks him if he received the “Sword of Honor,” which the younger man obviously invented on the spot. “No, no,” the major replies, “but I came close.”

Niven deservedly won the Best Actor award in 1958 for his role as Pollock, who regales his companions with embellished stories of his World War II exploits. Most viewers will immediately sense his duplicity. Before he’s spoken a word—in his “walk-on” introduction, in fact—he abruptly adopts an extroverted swagger and a different twirl of his walking stick. A young student, Charles (Rod Taylor), is also onto Pollock. When the major boasts of attending a couple of military schools, Charles asks him if he received the “Sword of Honor,” which the younger man obviously invented on the spot. “No, no,” the major replies, “but I came close.”

The young Australian actor Taylor, along with the two Americans, Lancaster and Hayworth, is part of an otherwise British cast. Charles and his girl friend, Jean (Irish actress Audrey Dalton), are lovers who prompt Mrs. Railton-Bell to whisper, “Quite obvious they were making love.” Railton-Bell’s mousy hanger-on, Lady Matheson (Cathleen Nesbitt), responds excitedly, “How do you know?” Jean pesters Charles to “go for walks” and jabs him in the shoulder, saying “bed, bed, bed,” but he feigns a preference for his books, though seems easily persuaded otherwise.

Mrs. Railton-Bell wastes no time in gathering a forum of the residents in an attempt to expel Pollock. Malcolm at first makes light of the allegations, trying to established exactly how many “nudges” the major gave various young women in the movie theater, then eloquently defends him, suggesting that Pollock’s lies about his war record are no worse than those told by others, individuals “here in this very room.” He looks at Ann. In the end, the final decision is the hotel manager’s, and Pat tells the major he may stay if he likes.

Mrs. Railton-Bell wastes no time in gathering a forum of the residents in an attempt to expel Pollock. Malcolm at first makes light of the allegations, trying to established exactly how many “nudges” the major gave various young women in the movie theater, then eloquently defends him, suggesting that Pollock’s lies about his war record are no worse than those told by others, individuals “here in this very room.” He looks at Ann. In the end, the final decision is the hotel manager’s, and Pat tells the major he may stay if he likes.

The real test comes the next morning at the breakfast table when Pollock faces his fellow residents. It’s presumed that Mrs. Railton-Bell’s influence will produce a collective snub from everyone, but the residences, one after the other, approach Pollock’s table and speak to him—Fowler about sports, Miss Meacham about the weather, Lady Matheson with a menu suggestion. All to the indignation of Mrs. Railton-Bell. Even Sibyl, whose own insecurity has found empathy with the major’s, leaves her mother’s table and chats with him about having seen the New Moon. For the first time, she has defied her mother; it is the triumph of the movie.

Miss Cooper tells Major Pollock that his taxi has arrived. He asks her to send it away. “Lunch at the usual time, then?” she asks. “Lunch at the usual time,” he replies.

.