“Compose a piece yourself, my dear, and see how it sounds to you after listening to Beethoven.”

—Claude Rains to Bette Davis

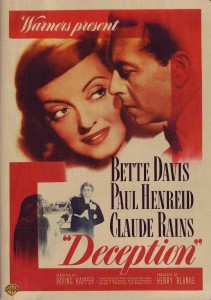

No, not the 2008 erotic, B-movie starring Hugh Jackman and Michelle Williams, which has little creativity or originality for the intelligent viewer, nor the 1993 mystery of the same name with Liam Neeson and Addie MacDowell. The 1946 Deception is a quite different flick, a crossbreed of genres—an often over-the-top drama through the theatrics of its three stars; a film noir, because of Ernest Haller’s chiaroscuro cinematography and Anton Grot’s angular art direction; a slippery soap opera, sometimes dignified as “a woman’s picture”; and, were it not so slowly paced and its single murder coming at the end, a thriller.

Since the three major stars, the director (Irving Rapper) and the studio (Warner Bros.) are identical in Now, Voyager, made five years earlier, perhaps a comparison between it and Deception would be an appropriate starting point in understanding the nature of the film, its strong points and its failings. In sum and despite all, Deception is a fascinating study, and for those with certain musical proclivities, a “must see” experience.

In Now, Voyager, Bette Davis’ salvation is Paul Henreid, whose presence and comfort make her life worthwhile. Davis’ new lease on life is due to her psychiatrist, Claude Rains, who transforms her from a mother-dominated, unattractive spinster to an independent, sophisticated woman. This film, by the way, contains one of Hollywood’s great lines: “Don’t ask for the moon,” Davis tells Henreid as they share a cigarette. “We have the stars.”

By contrast, in Deception, pianist Christine Radcliffe (Davis), already an attractive woman in the film—that’s not a problem here—keeps from Karel Novak (Henreid) the secret of her long-running affair with composer Alexander Hollenius (Rains), even after their marriage, until the last moments of the film when it’s too late. Now less a redeemer and protector, Henreid is an irresolute, suspicious cellist, near a nervous breakdown after his World War II experiences.

By contrast, in Deception, pianist Christine Radcliffe (Davis), already an attractive woman in the film—that’s not a problem here—keeps from Karel Novak (Henreid) the secret of her long-running affair with composer Alexander Hollenius (Rains), even after their marriage, until the last moments of the film when it’s too late. Now less a redeemer and protector, Henreid is an irresolute, suspicious cellist, near a nervous breakdown after his World War II experiences.

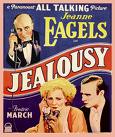

Deception is a remake of the 1929 Jealousy, starring Fredric March and Jeanne Eagels and based on a French play by Louis Vemeuil. There are subtle as well as major differences between the two films. In Jealousy, the husband, who is an artist, kills his wife’s former lover; in Deception, presumably to afford Davis a greater acting range, the wife kills her former lover. And everyone is a musician.

Deception is a remake of the 1929 Jealousy, starring Fredric March and Jeanne Eagels and based on a French play by Louis Vemeuil. There are subtle as well as major differences between the two films. In Jealousy, the husband, who is an artist, kills his wife’s former lover; in Deception, presumably to afford Davis a greater acting range, the wife kills her former lover. And everyone is a musician.

Which now justifies a study of what makes the film “fascinating” to viewers with a penchant for music, specifically classical music, classical music and more classical music. The works of J. S. Bach, Haydn, Schubert and Beethoven are interspersed throughout the movie. This assembly of such profoundly Teutonic voices, probably no coincidence, adds a sympathetic underpinning to the often ponderous histrionics of the characters.

The late George Korngold, one of two sons of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, called Deception “the only film about musicians that makes artistic sense.” Music is central to the plot and is often discussed in technical terms, and the film exposes the enormous egos and insecurities common to many musicians’ personalities.

The next quote is pertinent because it is about music and, more specifically, about Richard Strauss, who is mentioned in the film—and was alive in 1946. In Men of Music, Wallace Brockway and Herbert Weinstock denigrate Strauss’ 45-minute tone poem Ein Heldenleben as “constantly collapsing and falling over on its side like a backboneless leviathan. In the passing years, the little dead areas have spread until they now blotch the work like a devitalizing fungus.” Pretty verbose, eh? And picturesque——

Much like film critic Ted Sennett in a 1971 review: “Deception was even more ludicrous [than Davis’ A Stolen Life, also 1946], as she carried on operatically with Claude Rains and Paul Henreid to the loudest musical score Erich Wolfgang Korngold could devise. An unintentionally risible story of romantic discord among New York musicians, it featured hysterical quarrels in an apartment at least as large as Rhode Island, yards of high-toned dialogue about music and much ‘pseudo-classical’ (and dreadful) music, ostensibly written by that great composer Alexander Hollenius (Rains).” Rhode Island, indeed! And, by the way, there are two apartments, though, agreed, equally large.

Maybe not the best way to introduce Korngold to these proceedings. Deception was his last original film score—and, as background music per se, contains the least amount of music he ever wrote for a movie. The theme of the majestic main title (just below), with emphatic use of the tubular bells, appears throughout the film and exists two-dimensionally, both as murky background score and as resolute source music for the cello, whether played on that instrument or on the piano. The music behind dialogue is recorded at so low a volume as to approach inaudibility, hardly Korngold’s “loudest musical score.”

Maybe not the best way to introduce Korngold to these proceedings. Deception was his last original film score—and, as background music per se, contains the least amount of music he ever wrote for a movie. The theme of the majestic main title (just below), with emphatic use of the tubular bells, appears throughout the film and exists two-dimensionally, both as murky background score and as resolute source music for the cello, whether played on that instrument or on the piano. The music behind dialogue is recorded at so low a volume as to approach inaudibility, hardly Korngold’s “loudest musical score.”

In the film, the cello concerto is the work of Hollenius, who, as Karel observes when queried by a student journalist, “combines the rhythm of today with the melody of yesterday.” Forget that the actual composer, a pure romantic like Korngold, is trying to sound modern (“modern” in ferocity, perhaps, not so in tonality), supposedly as Hollenius would sound; forget that, as such, the music seems tame alongside what Schoenberg, Webern and Berg had done long before 1946. In its own right, the concerto is strikingly original.

If the wall-to-wall dialogue isn’t formidable enough, the centerpiece of the film—no disrespect to the three stars—is the ever-looming concerto. The instrument—its sound, its use, its discussion—dominates, distorts and demoralizes the lives of those who come in contact with it. In the opening of the film, the cello is already a competing “player” when Davis enters a concert hall. The tones of Haydn’s D-Major Concerto are heard before Davis utters her first word.

Much has been said—and most of it warranted—that Bette Davis commands center attention in all the films she made. This is clearly true in All About Eve, Jezebel, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, The Little Foxes and The Letter, to name the most obvious. But in Deception, despite what has been said about her dominance over her male stars, she is up against Claude Rains, who clearly steals the show. He received a Best Supporting Actor nomination that year, not for Deception but for another negative-titled film, Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious. He should have won, in deference to Harold Russell for The Best Years of Our Lives.

Much has been said—and most of it warranted—that Bette Davis commands center attention in all the films she made. This is clearly true in All About Eve, Jezebel, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, The Little Foxes and The Letter, to name the most obvious. But in Deception, despite what has been said about her dominance over her male stars, she is up against Claude Rains, who clearly steals the show. He received a Best Supporting Actor nomination that year, not for Deception but for another negative-titled film, Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious. He should have won, in deference to Harold Russell for The Best Years of Our Lives.

In at least three scenes, Rains presides supreme: his crashing of Davis and Henreid’s wedding party, the should-be-famous restaurant tour de force and the bedroom showdown with Davis, he in bed reading the Sunday comics. In the party scene belongs the cryptic lines, “Sooner or later you’ll come back to your old teacher. You’ll realize that nothing really matters but music. Everything passes but music—and me.”

Talking on the telephone in the movies has always been a dramatic occasion, a chance for women, especially, to act their hearts out. There’s Barbara Stanwyck in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948), Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove (1964), Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train (1951), the mute Dorothy McGuire in The Spiral Staircase (1946) and Ross Martin in Experiment in Terror (1962). The list is endless. Ingrid Bergman appeared in a 1967 TV production of Jean Cocteau’s The Human Voice (La voix humaine, 1930), and Francis Poulenc, in 1959, wrote a 50-minute mini-opera based on the same source.

Before Hollenius first appears at the wedding party, Christine receives a telephone call from him; his half of the conversation is not heard. During what is, in effect, a monologue, she calls him “Alex” until Karel comes home, when she illogically says “Hollenius”—not too smart a move for a woman trying to keep the ex-lover a secret, but, of course, the script required that Karel learn that she knows him.

In their first meeting after the party, Christine enters Hollenius’ extravagant hotel suite—perhaps only a parcel of Rhode Island!—as he’s ending a piece on the piano (dubbed by Korngold). “So you remember the concerto I started last winter,” he says. “Well, I finished it.” After he indicates he still can’t live without her, married or not, and she explains Karel’s unexpected return and unstable mental state, Hollenius seems to soften. “He’s something of a genius, you tell me—if the term can be applied to a performer.” (Much as the great Artur Rubinstein resented the application of the word “genius” to himself as a pianist.)

A few hours later Karel visits Hollenius, who falsely denies he phoned Christine a second time the night before and, lying further, says his previous visitor had been “masculine, my dear fellow, masculine.” The composer plays an old, pre-war recording of Karel’s and suggests, that if he plays this well, he, Hollenius, has a certain piece that might interest him.

Returning from practicing the cello part with Hollenius, in another extended scene (they’re all “extended”!), Karel shares with Christine his experience, both condemning and praising the egomaniacal composer. He says Hollenius has given him the concerto to study and, later, to perform publicly. His self-confidence seems restored.

Returning from practicing the cello part with Hollenius, in another extended scene (they’re all “extended”!), Karel shares with Christine his experience, both condemning and praising the egomaniacal composer. He says Hollenius has given him the concerto to study and, later, to perform publicly. His self-confidence seems restored.

Man and wife converse against a wall of picture windows, common in Manhattan penthouses at the time, it would seem, or at least in the movies of the ’40s, i.e., The Fountainhead (1949) and Rope, made in 1948 by Hitchcock. Rain running down the great window adds to the dreariness of the moment and underlines Christine’s still kept secret. Despite the Hollywood symbolism of water as a moral or physical cleansing, nothing is resolved or rectified.

Before the dress rehearsal, Hollenius hosts a dinner at a posh restaurant, ordering and reordering the meal in an attempt to unnerve his cellist. “Oh,” he says with mock sincerity, “I do hope the great haste with which we’re assembling this slapdash repast is not going to affect me internally and render me incapable of appreciating good music.” Hollenius is annoyed that Karel started his study of the concerto at the beginning and not with the fugato—“fugato,” another musical term thrown out as nonchalantly as any other dialogue. The punch line of the episode is delivered by Hollenius. After having finally settled, presumably, on a woodcock and establishing its accouterments—“Now, with a woodcock, with a woodcock . . . ,”—as they leave the restaurant, he muses, “Maybe we should’ve had the woodcock.”

With Karel at the rehearsal, Christine is alone in her penthouse. Pacing and going to the phone without making a call, she turns off the radio, just after it emits a commercial jingle typical of the time, about double magic Drawrof. The announcer boasts, “Remember, folks, when you spell ‘Drawrof’ backwards it reads ‘forward.’ ” Interrupting her pacing, Christine, with one finger, idly picks out a tune on the piano: it is the main theme from the cello concerto. Is she thinking of the rehearsal or of Hollenius?

With Karel at the rehearsal, Christine is alone in her penthouse. Pacing and going to the phone without making a call, she turns off the radio, just after it emits a commercial jingle typical of the time, about double magic Drawrof. The announcer boasts, “Remember, folks, when you spell ‘Drawrof’ backwards it reads ‘forward.’ ” Interrupting her pacing, Christine, with one finger, idly picks out a tune on the piano: it is the main theme from the cello concerto. Is she thinking of the rehearsal or of Hollenius?

Suspicious of Hollenius’ generosity in offering the solo cello part to her husband, Christine returns to the composer’s hotel suite. Hollenius, weary of her paranoia barrages, insists that her behavior is nothing new. “My dear, if you knew how many daggers I’ve had flourished before me by hysterical ladies of the opera—an earlier period of my life.” (For those viewers who look for continuity flubs, in one camera shot Rains puts down the Sunday comics and an instant later, in the next cut, he’s still holding the newspaper.) At any rate, Hollenius promises Christine he won’t withdraw Karel’s right to premiere the concerto.

The scripted arguments between Christine and Hollenius are so muddled that the viewer is never totally sure whether or not he plans to seek revenge against her by demoralizing Karel, or if the notion is confined to Christine’s own paranoid suspicions, or if the composer, not malevolent in the beginning, is given such an idea by her fears, or if——

The dress rehearsal begins calmly enough until Hollenius stops the orchestra. “The flute is ahead,” he says. “Have you no feeling for rhythm?” The passage is repeated. When Hollenius stops the orchestra again for the same infraction, Karel indignantly continues to play. A whack of the baton silences the cello. “I was under the impression,” Karel fumes, “this was a dress rehearsal. After all, this is a cello concerto, not a flute concerto.” Whereupon Hollenius asks him to leave the stage and replaces him with the first chair cellist, appropriately named Bertram Gribble (John Abbott), who provides, here and later, some welcomed comic relief. Christine, observing from a theater seat, is anxious for Karel, but when Hollenius comments, “We mustn’t exhaust the delicate creature for this evening’s performance,” she is relieved—for the moment.

The dress rehearsal begins calmly enough until Hollenius stops the orchestra. “The flute is ahead,” he says. “Have you no feeling for rhythm?” The passage is repeated. When Hollenius stops the orchestra again for the same infraction, Karel indignantly continues to play. A whack of the baton silences the cello. “I was under the impression,” Karel fumes, “this was a dress rehearsal. After all, this is a cello concerto, not a flute concerto.” Whereupon Hollenius asks him to leave the stage and replaces him with the first chair cellist, appropriately named Bertram Gribble (John Abbott), who provides, here and later, some welcomed comic relief. Christine, observing from a theater seat, is anxious for Karel, but when Hollenius comments, “We mustn’t exhaust the delicate creature for this evening’s performance,” she is relieved—for the moment.

An interesting footnote: Like any non-musician, Rains was coached in the proper gestures and baton use of a conductor, as was Charlton Heston for a similar role in Counterpoint (1968), not, by any means, a “film about musicians that makes artistic sense.” Rains is quite credible, with graceful arm sweeps and the characteristic grimaces and emoting of most real conductors; by contrast, Heston’s arm movements are painfully unmusical, his face expressionless.

Bette Davis, a trained pianist, wanted to play the Beethoven “Appassionata” Sonata at the wedding party, but, in the end, the concert pianist Shura Cherkassky laid down the track.

As for the ruse engineered for Henreid to “play” in close-ups, with his arms tied behind his back, two real cellists crouched behind him. One man’s left arm went through the left coat sleeve to simulate finger board action, the other’s right arm filled the right sleeve to handle the bow. The cello heard on screen is that of first cellist of the Warner Bros. orchestra, Eleanor Aller Slatkin, who gave the world premiere of the work in its final, revised form with the Los Angeles Philharmonic in late December, 1946.

It could justifiably be said that, in the acting awards, Rains is also the winner in his final appearance with Davis, even though he’s subdued and philosophical much of the time, spouting the best line in the film: “Compose a piece yourself, my dear, and see how it sounds to you after listening to Beethoven.” Pretty good, this “high-toned dialogue”! Dressed in black as she was in the opening scene, Christine now has a pistol: her fear that Hollenius will divulge her illicit secret has driven her to a final, terrible solution.

justifiably be said that, in the acting awards, Rains is also the winner in his final appearance with Davis, even though he’s subdued and philosophical much of the time, spouting the best line in the film: “Compose a piece yourself, my dear, and see how it sounds to you after listening to Beethoven.” Pretty good, this “high-toned dialogue”! Dressed in black as she was in the opening scene, Christine now has a pistol: her fear that Hollenius will divulge her illicit secret has driven her to a final, terrible solution.

In the film’s last scene, Christine arrives late to hear Karel perform the concerto, just as she was late to the film’s opening concert. After all the lies and even now, at the eleventh hour, Christine cannot tell her husband about that great deception of the film’s title—at least at first.. For a while, she concocts more lies. Finally, though, she reveals her affair—and that she has killed Hollenius. Karel is shocked at first—“How could you?”—then, perhaps as proof of his love for her, which conceivably is greater than hers for him, he suggests that going to the police might be a recourse.

The concerto and Karel’s playing were successes and it’s implied he’ll be re-engaged. As they leave the hall amid congratulations from the crowd, a woman gushes, “You must be the happiest woman in the world.”

On a final note, here is the original trailer from 1946.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hmBvAR7ArRU