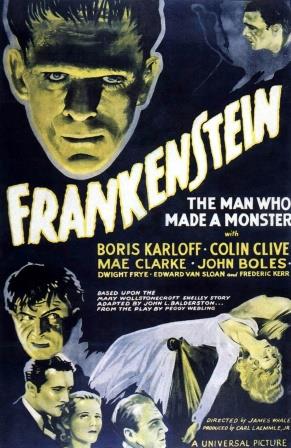

THE MAN WHO MADE A MONSTER

“Mr. Carl Laemmle feels it would be a little unkind to present this picture without a word of friendly warning,” begins Edward Van Sloan, one of the stars of the upcoming movie, speaking from the screen. Standing meekly on a stage, he further cautions his audience that the following is about a man of science who creates a human in his own image—without the help of, or even acknowledging, God. Van Sloan declares the movie “might even horrify you,” that for those with sensitive “nerves” now is their chance to leave. “ . . . well, we’ve warned you.”

To the sophisticated movie-goers of today, these warnings must seem unnecessary, ridiculous, even silly, but, remember, 1931, when Frankenstein was released, was a much more innocent time, though not to many living it. Sure, there had been that little engagement, World War I, the sexual and musical explosions of the Jazz Age, the gangsters, the drinking excesses to circumvent Prohibition and the Great Depression. But it was only a lull, for worse turmoil was yet to come—in an even more terrible world war; for the U.S., civil riots and a disastrous, lost war; and, worldwide, a Cold War and, now, terrorism.

Soon after the initial release of Frankenstein, the scientist’s line, “Now I know what it’s like to be God!,” spoken after his monster creation, was excised because of the suggested blasphemy and the moral temper of the times. The line was restored in the DVD release. In a later scene the monster comes upon a little girl and, together, they throw flowers into a lake. When there are no more flowers, it throws her into the lake, then walks away confused that she didn’t float like the petals—this was also cut and restored many years later.

Upon its initial release, the film was banned in Kansas because it showed “cruelty and tended to debase morals.”

Upon its initial release, the film was banned in Kansas because it showed “cruelty and tended to debase morals.”

After more than eighty years and the astonishing advances of 21st-century computer technology, coinciding with the demand for more gore and the sensational, Frankenstein does creak at times, seems quaint and, to some, as out of date as a silent film. The occasional stilted and stagy acting merely mirrors the film’s other early ’30s elements; the time wasn’t all that removed from the techniques of those older movies. For the many scenes that are stunning but somehow seem “naked” and in need of support, the absence of a score, other than main and end titles, is the film’s chief weakness.

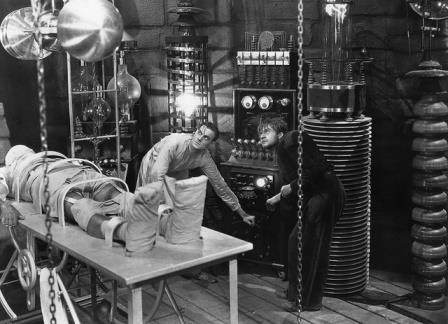

Still, Frankenstein, whatever its flaws, has the power to impress, even frighten first-time viewers, as it frightened many viewers in 1931. While nothing jumps out to frighten—not even the monster’s introduction—or labors for momentary sensation, the film impresses through its consistent and artful milieu. This atmosphere comprises the pencil-sharp contrasts of black-and-white in the cinematography of Arthur Edeson (The Maltese Falcon [1941], Casablanca [1942], etc.); the stark back-lighting, especially in graveyard and forest scenes; the heavy German Expressionism in both lighting and in the watchtower interiors; and the stunning electrical effects by Ken Strickfaden when the assembled cadaver is lifted to the top of the tower.

Henry Frankenstein’s lab, with its assembled electronic façade, which is attached to nothing and does nothing except look exotic, was borrowed by Mel Brooks almost forty-five years later for his Young Frankenstein parody. In many respects, that film, comedy or not, comes as close as any in its conscious endeavor to recapture the essence of the original—chiefly through its sets, lighting and a score by John Morris which, if sometimes overblown, imagines what Frankenstein might have sounded like in 1931 with music.

Henry Frankenstein’s lab, with its assembled electronic façade, which is attached to nothing and does nothing except look exotic, was borrowed by Mel Brooks almost forty-five years later for his Young Frankenstein parody. In many respects, that film, comedy or not, comes as close as any in its conscious endeavor to recapture the essence of the original—chiefly through its sets, lighting and a score by John Morris which, if sometimes overblown, imagines what Frankenstein might have sounded like in 1931 with music.

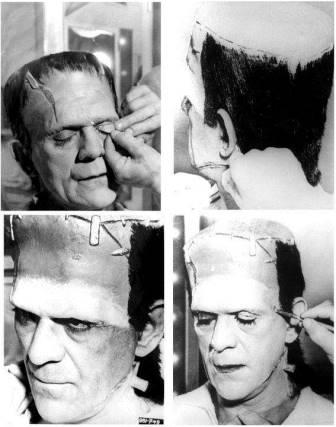

Before Frankenstein began filming, and under Robert Florey’s direction, Bela Lugosi had made a twenty-minute test, now believed lost, but Lugosi disliked the lack of dialogue and being unrecognizable beneath Jack Pierce’s thick makeup. John Carradine, who, rumor has it, said he was offered a test, regarded himself as too high-class an actor for such a degrading part. Boris Karloff made some seventy-five, now generally forgotten films before director James Whale approached him in the Universal commissary and offered him a test. This “monster movie” would put him on the Hollywood map at age forty-four; today, star and film are thought of as one. Since the actor was limited to only a few guttural and animal noises and hindered by face-concealing makeup, the stiff costume and heavy shoes (thirteen pounds each), he was limited to arm/hand gestures and his eyes for expression.

Encumbered with a creature of little intelligence or moral sense, Karloff made it sympathetic, a being pleading for understanding, struggling against the abuses of its creator and finding friendship in the eyes of a little girl who did not fear him. In the creature’s reincarnation in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), it would find another friend, if only briefly, in the also unfrightened old hermit (O. P. Heggie), who would teach him music and that fire could be good.

Encumbered with a creature of little intelligence or moral sense, Karloff made it sympathetic, a being pleading for understanding, struggling against the abuses of its creator and finding friendship in the eyes of a little girl who did not fear him. In the creature’s reincarnation in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), it would find another friend, if only briefly, in the also unfrightened old hermit (O. P. Heggie), who would teach him music and that fire could be good.

The producer Carl Laemmle, Jr., mentioned in Van Sloan’s introduction, once said, “Karloff’s eyes mirrored the suffering we needed.” Mae Clarke, who played the scientist’s fiancée, recalled, “When [Karloff] looked up and up and up and up and waved his hand at the light [from the skylight], it was a spiritual lesson, looking at God!”

Laemmle, son of the founder of Universal Pictures, produced 149 movies between 1926 and 1936. The titles represent some of the great pre-1940s Universal horror films, including Dracula (1931), Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932),The Old Dark House (1932), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1932), The Black Cat (1934) and The Bride of Frankenstein; and, in addition, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and Showboat (1936), before he was ousted as in charge of production. An impressive list.

Laemmle, son of the founder of Universal Pictures, produced 149 movies between 1926 and 1936. The titles represent some of the great pre-1940s Universal horror films, including Dracula (1931), Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932),The Old Dark House (1932), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1932), The Black Cat (1934) and The Bride of Frankenstein; and, in addition, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and Showboat (1936), before he was ousted as in charge of production. An impressive list.

As impressive, for a while at least, as are the films of James Whale. While the likes of Billy Wilder and William Wyler could consistently pull great movies out of their hats over a forty-year career, Whale was considerably less productive, and suffered a sharp decline when he lost influence at Universal. Within a four-year period, however, he did produce a string of greats—all horror: Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, The Invisible Man and The Bride of Frankenstein; later, in 1939, there would be one last flourish in the genre, The Man in the Iron Mask.

As impressive, for a while at least, as are the films of James Whale. While the likes of Billy Wilder and William Wyler could consistently pull great movies out of their hats over a forty-year career, Whale was considerably less productive, and suffered a sharp decline when he lost influence at Universal. Within a four-year period, however, he did produce a string of greats—all horror: Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, The Invisible Man and The Bride of Frankenstein; later, in 1939, there would be one last flourish in the genre, The Man in the Iron Mask.

For the time of the story, Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, indicates the eighteenth century; the film fluctuates between dress and interior sets of the 1930s and what could be any time in oldGermany for the villagers. Set in Europe at any rate.

Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and his hunchback assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye) hide until the end of a funeral. A hidden microphone amplifies the sound of the dirt hitting the coffin lid—one of many examples of the film’s emphasis on sound, still a relative novelty in 1931. The gravedigger finished, he lights a cigarette, tosses the match irreverently on the grave, throws his coat over his shoulder and strolls away, across the rim of a hill, silhouetted against an ashen sunset.

Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and his hunchback assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye) hide until the end of a funeral. A hidden microphone amplifies the sound of the dirt hitting the coffin lid—one of many examples of the film’s emphasis on sound, still a relative novelty in 1931. The gravedigger finished, he lights a cigarette, tosses the match irreverently on the grave, throws his coat over his shoulder and strolls away, across the rim of a hill, silhouetted against an ashen sunset.

Henry and Fritz dig up the coffin and cart it away. Later, the brain of a corpse cut down from a scaffold proves unusable. At a medical college, Fritz drops and breaks the formaldehyde bowl marked “normal brain” and substitutes another, marked “abnormal.”

Concerned about her fiancé’s strange seclusion in his laboratory in a rundown watchtower, Elizabeth (Clarke) learns from Dr. Waldman (Sloan) that Henry is working on creating life from the dead, assembling a body from various corpses. He has discovered, he says, “the great ray that first brought life into the world.”

In the midst of a thunderstorm (utilizing for the first time the actual sound of a thunderclap, called “Castle Thunder,” an effect used in many later films), Henry and Fritz raise the amalgamated corpse on an operating table to the top of the tower. Elizabeth and Waldman watch as the storm rages, electronic machines crackle and tubes arc—a feast for the ears and eyes. When the table is lowered, the corpse’s right hand moves. “It’s alive! It’s alive!” Henry cries, bracing himself on the table and turning to face the camera and shouting as if for all to hear—those in the lab, in the audience, in the entire world. “Now I know what it’s like to be God!”

In the midst of a thunderstorm (utilizing for the first time the actual sound of a thunderclap, called “Castle Thunder,” an effect used in many later films), Henry and Fritz raise the amalgamated corpse on an operating table to the top of the tower. Elizabeth and Waldman watch as the storm rages, electronic machines crackle and tubes arc—a feast for the ears and eyes. When the table is lowered, the corpse’s right hand moves. “It’s alive! It’s alive!” Henry cries, bracing himself on the table and turning to face the camera and shouting as if for all to hear—those in the lab, in the audience, in the entire world. “Now I know what it’s like to be God!”

The first appearance of the monster, seen earlier only as a corpse in bandages, is dynamically and dramatically controlled by director Whale. First, there is only the sound, again amplified, of shuffling feet. A door opens and a hulking figure backs into the room. The audience is being teased, a frontal view delayed. In a head-and-shoulder shot, the head turns slowly, deliberately, only a half-turn at first. A stream of light falls on half, then on the full face. A close-up in two cuts reveals the black, heavy-lidded eyes, the pronounced brow and, above, the dome of an almost square, flat-topped head. The so-called “bolts” on the sides of the neck are actually electrodes. The shoes are huge and rectangular, the arms long and stiff, the hands extending starkly beyond the ends of heavy cuffs.

T he grotesque giant appears at first to be simple and childlike, and is able to obey simple commands. When Henry opens the skylight in the tower, the creature is fascinated by the bright sunlight streaming down, stretching both arms upward, its hands extending even more, the fingers spread, quivering, as if to capture the light, as if begging for help, for sympathy. Or maybe for deliverance from a new, alien world?

he grotesque giant appears at first to be simple and childlike, and is able to obey simple commands. When Henry opens the skylight in the tower, the creature is fascinated by the bright sunlight streaming down, stretching both arms upward, its hands extending even more, the fingers spread, quivering, as if to capture the light, as if begging for help, for sympathy. Or maybe for deliverance from a new, alien world?

But when Fritz torments the monster with a torch, it becomes both frightened and vicious. The creature is locked away, but it kills Fritz when he again taunts it with fire, and, later, when Henry and Waldman decide the thing must be destroyed, it strangles Waldman as he prepares to dissect it.

Escaping the watchtower, the creature wanders the woods and comes upon a farmer’s seven-year-old daughter (Marilyn Harris). Unafraid, she says, “I’m Maria. Will you play with me?,” and takes its hand. (Indeed, the little actress herself was unafraid when first seeing Karloff in his full makeup.) The monster, reverting to its childlike demeanor, thrills at floating flowers in the lake—until the flowers run out, with that tragic result.

Escaping the watchtower, the creature wanders the woods and comes upon a farmer’s seven-year-old daughter (Marilyn Harris). Unafraid, she says, “I’m Maria. Will you play with me?,” and takes its hand. (Indeed, the little actress herself was unafraid when first seeing Karloff in his full makeup.) The monster, reverting to its childlike demeanor, thrills at floating flowers in the lake—until the flowers run out, with that tragic result.

After Henry and Elizabeth have been married, the monster enters her room. She faints and it escapes. (Interesting, if not a cinema first, the camera dollies among several rooms, even passing through a wall.) Moments later news arrives of Waldman’s murder, then the farmer walks through the village carrying the body of Maria.

Divided groups search for the monster. Henry, leading his party in the mountains, comes across it. (In several shots, the ripples in a scenic backdrop curtain are clearly visible.) The monster knocks Henry unconscious and carries him to the top of an old windmill and hurls him (clearly a dummy) from the porch. His fall is broken by a vane of the windmill.

Divided groups search for the monster. Henry, leading his party in the mountains, comes across it. (In several shots, the ripples in a scenic backdrop curtain are clearly visible.) The monster knocks Henry unconscious and carries him to the top of an old windmill and hurls him (clearly a dummy) from the porch. His fall is broken by a vane of the windmill.

While the injured Henry is hurried off to his home, the creature once again encounters its great fear, fire, which the villagers have started. Inside the windmill, it frantically struggles against the conflagration and is finally pinned beneath a burning timber.

In a rather comic, letdown conclusion, six maids—the former bridesmaids?—knock on Henry’s bedroom door with some wine. His father (Frederick Kerr) opens the door—beyond, Elizabeth is sitting beside her convalescing husband—and says he’s the one who needs a drink and toasts some future son of the House of Frankenstein.

“A good cast is worth repeating . . . ” heads the end cast title. In the opening cast listing there was only “The Monster . . . ?” Now it’s “The Monster . . . Boris Karloff.” The actor was so ignored at Universal, despite those seventy-five films, that he was not invited to the December 6th premiere. Not only would the monster somehow survive death at the windmill, but Karloff would play the creature in two subsequent films—Son of Frankenstein (1939) and one of the great horror films, The Bride of Frankenstein.

“A good cast is worth repeating . . . ” heads the end cast title. In the opening cast listing there was only “The Monster . . . ?” Now it’s “The Monster . . . Boris Karloff.” The actor was so ignored at Universal, despite those seventy-five films, that he was not invited to the December 6th premiere. Not only would the monster somehow survive death at the windmill, but Karloff would play the creature in two subsequent films—Son of Frankenstein (1939) and one of the great horror films, The Bride of Frankenstein.

Karloff—fortunately—for the rest of his life never escaped his horror association—and well that he didn’t. “The monster,” he said, “was the best friend I ever had.”