“ . . . NOT FAR FROM NEW ORLEANS, THERE STILL EXIST, IN STRANGE SOLITUDE, THE BAYOUS OF LOUISIANA . . . ”

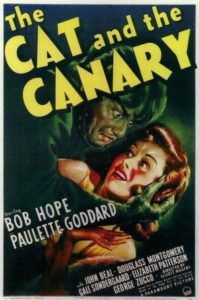

By various means, by rowboat, motorboat or rather inexplicably appearing at the front door, seven people arrive at a spooky old mansion among cypress and oak trees heavily draped with moss. The first arrival, a lawyer, tells his boatman to return for him in two hours. “No more ride for you tonight,” the Indian (George Regas) replies. “Tomorrow.” Ominous, eh? Soon after, the sinister Creole housekeeper and believer in spirits, tells the lawyer, “The house is full of murmurs.” Later, when all the guests have arrived, she prophesies, “There are eight people in this room. One will die before morning.” If it sounds all too familiar, the tone for this particular movie, The Cat and the Canary (1939), is nevertheless set. . . .

The standard for this kind of talking picture was set in 1932, with James Whale’s The Old Dark House, where an assorted group of people are isolated in a creepy old house on a stormy night. The film, the second of Whale’s great horror epics (all short, but “epics” nonetheless; the first being Frankenstein), became the prototype for this type of mystery, of which there have been many—and many more, to the point where, now, a different, original approach is almost impossible. The label, “an old dark house” mystery, much like another cliché, “it was a dark and stormy night,” has entered the accepted lexicon when referring to this kind of movie.

Closing in on the subject at hand, this same plot predated the Whale film in the 1927 silent version of The Cat and the Canary, with Laura LaPlante and Tully Marshall. Retitled The Cat Creeps in 1930, the same story line included the veteran of “old lady” parts, Elizabeth Patterson, who would star in still another take on the same material in 1939, now back-titled to The Cat and the Canary.

Two rather dismal British remakes would follow: The Old Dark House (1963) featured Robert Morley and Tom Poston, and, once again that title, The Cat and the Canary (1978) starred Edward Fox and Wendy Hiller. Neither of two pictures entitled The Black Cat, in 1934 and 1941, starring, respectively, Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi and Basil Rathbone and Hugh Herbert, would feature a feline central to the plot, but, again, the scenario was the gathering of a group of people in, yep, an old dark house. The list of movies on this theme is endless.

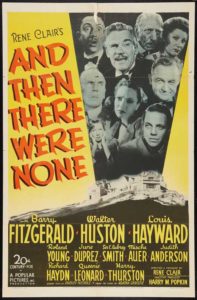

And Agatha Christie, either in the books or their transfer to film, wouldn’t exist without a dozen suspects gathered at an old house, whether in “The Mysterious Affair at Styles”, ”Peril at End House” or “Murder for Christmas”. A Christie house need not be just “dark”—it might also be isolated, as in “And Then There Were None”, itself filmed four times, thrice under the title Ten Little Indians. But enough!

And Agatha Christie, either in the books or their transfer to film, wouldn’t exist without a dozen suspects gathered at an old house, whether in “The Mysterious Affair at Styles”, ”Peril at End House” or “Murder for Christmas”. A Christie house need not be just “dark”—it might also be isolated, as in “And Then There Were None”, itself filmed four times, thrice under the title Ten Little Indians. But enough!

Where, in all this exposition, is the link—and there is one!—to the subject? Why, Elizabeth Patterson. Because, in the aforementioned 1939 The Cat and the Canary, she plays a nervous Nellie character named Aunt Susan. Living to be ninety, Patterson is perhaps best remembered as Mrs. Trumbull, Lucille Ball’s neighbor in the I Love Lucy TV series (1952-56).

Though more anxious for adventure, Patterson’s companion in fright in The Cat and the Canary is the delightful Nydia Westman. From 1932, the actress spent fifteen years in the movies before concentrating on Broadway and television. She was a TV regular on Going My Way and Dragnet 1967, and made appearances on Perry Mason, My Favorite Martian, Bonanza and The Munsters. Westman did, however, continue to make occasional theatrical films, and one, The Ghost and Mr. Chicken (1966), with Don Knotts, was another variant, now ultra slapstick, on the old dark house plot.

The two ladies, in minor roles to be sure, have good starring support, starting with the top-billed Bob Hope. Although he is yet the central character of the film, as he would become later in his career, this is his seventh movie to date, the hit that made him a screen fixture—and super star—at least solidly for the 1940s and part of the ’50s. Here he continues to perfect the image that typifies most of his roles and where he felt the most comfortable (a limited acting range, to be sure), that of the coward masquerading as a debonair hero, often a ladies’ man, the way, indeed, Hope saw himself in real life. His timing and gestures in The Cat and the Canary are perfect, and he keeps coward and hero in a delicate balance, each always present, only in varying proportions.

The two ladies, in minor roles to be sure, have good starring support, starting with the top-billed Bob Hope. Although he is yet the central character of the film, as he would become later in his career, this is his seventh movie to date, the hit that made him a screen fixture—and super star—at least solidly for the 1940s and part of the ’50s. Here he continues to perfect the image that typifies most of his roles and where he felt the most comfortable (a limited acting range, to be sure), that of the coward masquerading as a debonair hero, often a ladies’ man, the way, indeed, Hope saw himself in real life. His timing and gestures in The Cat and the Canary are perfect, and he keeps coward and hero in a delicate balance, each always present, only in varying proportions.

His leading lady, Paulette Goddard, who, by the way, was unimpressed by his off-screen Don Juan posturing, receives second billing below Hope’s name. Once the leading contender for the role of Scarlett in Gone With the Wind, by the time of The Cat and the Canary’s release, in November, 1939, she had long been passed over in favor of Vivien Leigh, and that film was within a month of being released.

His leading lady, Paulette Goddard, who, by the way, was unimpressed by his off-screen Don Juan posturing, receives second billing below Hope’s name. Once the leading contender for the role of Scarlett in Gone With the Wind, by the time of The Cat and the Canary’s release, in November, 1939, she had long been passed over in favor of Vivien Leigh, and that film was within a month of being released.

Despite Goddard’s feelings toward her co-star, she turns on her own brand of charm, to go with Hope’s, and, together, they make magical charisma. She is deliciously attractive. In the numerous moments requiring it, she is properly frightened—when people disappear, when a hand reaches out from a wall panel or when confronted by “The Cat”—but she is always careful to remain beautiful and strike an artful pose, even when running in terror through a cobweb-infested secret passage, dressed in a flattering white gown and always brightly lit.

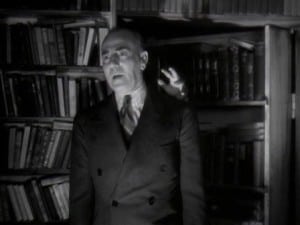

Also among the cast is George Zucco, the first to appear on screen. His mellifluous voice is always suggestive of malevolence, but here he becomes the film’s first victim. While Gale Sondergaard has a link to the 1941 The Black Cat and is often cast as a Zucco-like female equal in malice, here her glares, squinting eyes and trances are only deceptions, for she is not the villain, either. The would-be sleuths in the old mansion—and assumed suspects as well—will have to search elsewhere for the culprit.

Also among the cast is George Zucco, the first to appear on screen. His mellifluous voice is always suggestive of malevolence, but here he becomes the film’s first victim. While Gale Sondergaard has a link to the 1941 The Black Cat and is often cast as a Zucco-like female equal in malice, here her glares, squinting eyes and trances are only deceptions, for she is not the villain, either. The would-be sleuths in the old mansion—and assumed suspects as well—will have to search elsewhere for the culprit.

Hope’s two rivals for the affections of Goddard are Douglass Montgomery, who perhaps is best known for Little Women and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, and John Beal, who found greater success in television, most notably in Dark Shadows. He was in the 1935 Les Misérables with Charles Laughton; his last film, The Firm, in 1993, was with Tom Cruise.

The cast is filled out with John Wray; Chief Thundercloud, the logical player of Indians in a number of Westerns, and here one of the boatmen; and the long-lived Charles Lane for a few minutes at the end.

The Paramount picture is equally well supported by those responsible for what is seen and heard on screen, beyond the actors themselves. The director is the gifted Elliot Nugent, responsible for a number of other Hope films—Give Me a Sailor, Nothing But the Truth and one of his best, My Favorite Brunette. George Marshall, however, was Hope’s most frequent director, maybe because he was more in sync with the actor’s approach and could tolerate the egomania.

The Paramount picture is equally well supported by those responsible for what is seen and heard on screen, beyond the actors themselves. The director is the gifted Elliot Nugent, responsible for a number of other Hope films—Give Me a Sailor, Nothing But the Truth and one of his best, My Favorite Brunette. George Marshall, however, was Hope’s most frequent director, maybe because he was more in sync with the actor’s approach and could tolerate the egomania.

The cinematographer of The Cat and the Canary, Charles Lang, was nominated for seventeen Oscars and photographed some of Hollywood’s great films—The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, Separate Tables, Some Like It Hot and Charade. His atmospheric camera work is complemented by A. E. Freudeman’s art direction. Relegated to mostly B films, Freudeman’s name is connected with a few famous movies—the first of Hope’s seven Road pictures with Bing Crosby, The Road to Singapore, Lubitsch’s That Uncertain Feeling and Cecil B. DeMille’s Union Pacific. With the help of art directors German-born Hans Dreier, himself no slouch (The Long Weekend and Sunset Blvd.), and frequent collaborator, American Robert Usher, Freudeman surpasses even Universal in creating an evocative, ghostly atmosphere in The Cat and the Canary.

The film’s composer, Ernst Toch, is better known as a serious, “classical” composer, who fled Hitler’s Third Reich in the 1930s, and, like fellow émigré Freudeman, was consigned to B films. Occasionally he would serve as an orchestrator, but, more often than not, was nothing more than a provider of stock music and, almost always, uncredited on screen.

The film’s composer, Ernst Toch, is better known as a serious, “classical” composer, who fled Hitler’s Third Reich in the 1930s, and, like fellow émigré Freudeman, was consigned to B films. Occasionally he would serve as an orchestrator, but, more often than not, was nothing more than a provider of stock music and, almost always, uncredited on screen.

The Cat and the Canary is one of few pictures where Toch is given screen credit, here as “Dr. Ernst Toch.” Presumably, as it cannot be substantiated, he composed all the score. Behind the main title, he writes some immediately striking music, a trumpet motif that seems to call forth something strange and unknown. A pair of weather-worn shutters—the mildew and peeling paint on the louver boards can almost be felt—opens at the beginning of the credits; at the credit’s conclusion, the shutters close and the strings settle into an eerie tremolo as that first rowboat glides through a swamp toward . . . an old dark house. . . .

Millionaire Cyrus Norman died exactly ten years ago, and seven relatives arrive at his old mansion in the Louisiana bayous to hear the reading of the will by his lawyer Crosby (Zucco). The only person still possessing the Norman name is Joyce (Goddard), a sketch artist. Two men who had previous romantic interests in her are Charles Wilder (Montgomery) and Fred Blythe (Beal). Also an unintended “pair” are the two elderly ladies, Aunt Susan (Patterson) and Cicily (Westman). And then there is a comic actor, Wally Campbell (Hope), who had known Goddard in high school, but only remembers with his former classmate’s prodding.

Millionaire Cyrus Norman died exactly ten years ago, and seven relatives arrive at his old mansion in the Louisiana bayous to hear the reading of the will by his lawyer Crosby (Zucco). The only person still possessing the Norman name is Joyce (Goddard), a sketch artist. Two men who had previous romantic interests in her are Charles Wilder (Montgomery) and Fred Blythe (Beal). Also an unintended “pair” are the two elderly ladies, Aunt Susan (Patterson) and Cicily (Westman). And then there is a comic actor, Wally Campbell (Hope), who had known Goddard in high school, but only remembers with his former classmate’s prodding.

Besides the cliché of the grandfather clock that had stopped upon Cyrus’ death, the flickering lights and, later, the portrait with moving eyes, the housekeeper and former mistress of Norman, Miss Lu (Sondergaard) now responds to the spirit voices she alone hears and to the sounding seven times of an unseen gong. She warns that one of those gathered will die before morning.

Turns out, Joyce inherits the entire estate, but because of the insanity that runs in her family, the will stipulates that she must remain sane for thirty days; if not, the named person in a sealed envelope will become the heir. This, naturally, puts Joyce in danger should someone try to do her in or drive her crazy. Conveniently giving someone such a chance, the group must spend the night in the house, since boat transport will not be available until morning.

A security guard, Hendricks (Wray), from a nearby insane asylum turns up outside and warns that a psychotic killer, known as “The Cat,” has escaped. The guard appears rather abruptly and again later in a couple of scenes, without much explanation. Rather suspicious, eh? A red herring or could he be——?

A security guard, Hendricks (Wray), from a nearby insane asylum turns up outside and warns that a psychotic killer, known as “The Cat,” has escaped. The guard appears rather abruptly and again later in a couple of scenes, without much explanation. Rather suspicious, eh? A red herring or could he be——?

Later, while Wally and Cicily are investigating the cellar, there’s a chance for a Hope political joke. The comedian was never especially politically sophisticated; rather, being attuned to the political mood of the country provided comic material. Since, at the time, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt was half way through the second of three full terms and the Democrats controlled Congress, the line seemed only appropriate:

“It’s awful spooky down here,” Cicily says. “Do you believe in reincarnation?”

“Huh?” Wally responds, distracted by his fear.

“You know, that dead people come back?”

“You mean like the Republicans?”

As Crosby starts to warn Joyce about something, a section of the bookcase swings open and a hand reaches out and silently pulls him in, that portion of books then closing. Joyce’s back is to the bookcase and she’s mystified when she turns and finds Crosby gone. Everyone except Wally assumes she imagined it.

After deciphering a verse in an old Cyrus Norman letter and finding a diamond necklace in a secret access in the foundation of an abandoned fountain, that night Joyce puts the strand under her pillow. While she is half asleep, a hand emerges from a secret panel at the head of her bed and steals the necklace. Joyce becomes hysterical. Wally finds the secret panel—and, inside, a pull cord. “Listen, baby,” he says, “don’t be surprised if we discover an old skeleton in here!” He pulls the cord, a wall panel beside the bed slides back and Crosby’s body falls forward.

After deciphering a verse in an old Cyrus Norman letter and finding a diamond necklace in a secret access in the foundation of an abandoned fountain, that night Joyce puts the strand under her pillow. While she is half asleep, a hand emerges from a secret panel at the head of her bed and steals the necklace. Joyce becomes hysterical. Wally finds the secret panel—and, inside, a pull cord. “Listen, baby,” he says, “don’t be surprised if we discover an old skeleton in here!” He pulls the cord, a wall panel beside the bed slides back and Crosby’s body falls forward.

While Wally has gone for a bottle of Scotch to settle Joyce’s nerves, she sees the bookcase open and, curious, discovers a secret passage. Inside, she is stalked by a shadowy figure and once passes Hendricks, hidden in the shadows—his last turn as a possible red herring? When the figure, now seen with a cat face, passes Hendricks, the security guard takes the necklace from him, but is knifed in the back, presumably by the prison escapee, “The Cat.”

Joyce finds a door leading to the outside and escapes into a shed, “The Cat” behind her. Now Wally emerges to tell Joyce he’s found a clue. He confronts “The Cat” and calls out, “Charlie!” Charles Wilder removes a mask and frantically complains that Joyce has stolen his inheritance. He fights with Wally and pins him to the wall with his knife. As Wilder turns to choke Joyce, Miss Lu arrives and shoots him with a shotgun. “You poisoned old man Norman’s mind against me,” she declares.

Joyce finds a door leading to the outside and escapes into a shed, “The Cat” behind her. Now Wally emerges to tell Joyce he’s found a clue. He confronts “The Cat” and calls out, “Charlie!” Charles Wilder removes a mask and frantically complains that Joyce has stolen his inheritance. He fights with Wally and pins him to the wall with his knife. As Wilder turns to choke Joyce, Miss Lu arrives and shoots him with a shotgun. “You poisoned old man Norman’s mind against me,” she declares.

In the final scene, Wally, the haughty hero now in full bloom, is interviewed by reporters. He figured, he boasts, that whoever killed Crosby had to be the second heir—and he found the will’s sealed envelope in Wilder’s coat. After Joyce and Wally have announced their engagement, another reporter (Lane) asks how Wally knew “The Cat” was Wilder. He brags that he found a piece of sponge, like actors use in makeup, and knew that “The Cat” was wearing a mask. Moments later, having examined the “sponge,” Joyce says, no, that’s the eraser she uses in her sketching! After the usual double-take, long silence and delayed hysterics over his error, Wally kisses Joyce and all is well.

Similar to The Cat and the Canary, there would be, the next year, 1940, The Ghost Breakers, more comic and ghostly shenanigans in an old dark old house, again with Paulette Goddard, only with Marshall as director. Now, however, Hope would not only have top billing again, he would become what he always wanted, what he strove for all his life, to be the central character—in the movies, in anything, in all things. Already one of the most popular radio stars of the ’30s and ’40s, he would go on to greater heights, far greater—more and better movies (and, true, a lot of bad ones), television, entertaining servicemen overseas during three wars and “conflicts” and supporting any number of charities.

Similar to The Cat and the Canary, there would be, the next year, 1940, The Ghost Breakers, more comic and ghostly shenanigans in an old dark old house, again with Paulette Goddard, only with Marshall as director. Now, however, Hope would not only have top billing again, he would become what he always wanted, what he strove for all his life, to be the central character—in the movies, in anything, in all things. Already one of the most popular radio stars of the ’30s and ’40s, he would go on to greater heights, far greater—more and better movies (and, true, a lot of bad ones), television, entertaining servicemen overseas during three wars and “conflicts” and supporting any number of charities.

In his biography of Hope, Richard Zoglin wrote, “To many, he seemed hopelessly shallow: a gleaming perpetual-motion machine with a missing piece at the center.” But Zoglin also wrote: “ . . . there is hardly an element of our modern celebrity culture that Bob Hope did not invent, pioneer or help to popularize. He was largely responsible, in the age of celebrity, for setting the parameters of what it means to be a celebrity.”