Priscilla Lane has passed on Cary Grant! No wonder: she’s just discovered his favorite aunts have poisoned their 13th gentleman friend!

In these hard economic times, a little bit of escapism might be a good thing, almost essential, would you say? How better to escape than into a movie theater, or, okay, watch a DVD in a darkened room. Attending movies had worked miracles in mitigating everyday troubles during the Great Depression of the 1930s; why not now, during our current Small (so far) Depression, though “they” continue to call it a recession, not even yet with a large “r”? But how to escape into today’s movies?

Most of the present so-called “comedies” don’t do it for me: they’re too much encumbered by the contemporary climate which is either belittled or senselessly exaggerated. What about a comedy that is clearly removed from what’s happening at the moment? Oh, sure, this film I have in mind, and which I’ve just watched after some years’ abstinence, has a tie to our time. There are homeless men, political innuendo and cruelty to one another, among other things—see, nothing changes!—but, even more than being in black and white, the film has a certain old-fashioned remoteness, of another time. It’s removed from the “now” in the way today’s Tim Burton films exist in a fantasy nether world. Yes, not emotionally involving.

Arsenic and Old Lace is one of Frank Capra’s “oddest choices of material,” as Joseph McBride describes it in Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. “Odd” because it was the first sign of the director’s abandonment of his theme of social conscious, expressed so well earlier in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Meet John Doe. Arsenic was made in the last three months of 1941. As part of its agreement, Warner Bros. could not release the film until after the play had closed on Broadway—it ran for 1,444 performances—which was not until September of 1944, and then only after it had been shown first to the military.

Arsenic and Old Lace is one of Frank Capra’s “oddest choices of material,” as Joseph McBride describes it in Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. “Odd” because it was the first sign of the director’s abandonment of his theme of social conscious, expressed so well earlier in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Meet John Doe. Arsenic was made in the last three months of 1941. As part of its agreement, Warner Bros. could not release the film until after the play had closed on Broadway—it ran for 1,444 performances—which was not until September of 1944, and then only after it had been shown first to the military.

The film’s story, of course, is well known. The play by Joseph Kesselring (presumably unrelated to the German field marshal, Albert, of WWII!) is still popular fare among amateur college productions. Two elderly maiden sisters of the Brewster family, Abby (Josephine Hull) and Martha (Jean Adair), have been knocking off lonely old men with just the right mixtures of arsenic, strychnine and cyanide—disguised in elderberry wine. “When it’s in tea,” complains Martha, “it has a distinct odor.”

The victims are buried in the cellar, usually by the live-in nephew, Teddy (John Alexander), who, believing he’s Theodore Roosevelt, assumes he’s merely digging another lock for the Panama Canal. Whenever he goes upstairs—he’s often downstairs, either on a burial detail or handling matters of state—he draws an imaginary saber and cries “charge!,” ascending with appropriate clamor, prompting the grandfather clock beside the staircase to “dong” and drop its minute hand to six o’clock.

The victims are buried in the cellar, usually by the live-in nephew, Teddy (John Alexander), who, believing he’s Theodore Roosevelt, assumes he’s merely digging another lock for the Panama Canal. Whenever he goes upstairs—he’s often downstairs, either on a burial detail or handling matters of state—he draws an imaginary saber and cries “charge!,” ascending with appropriate clamor, prompting the grandfather clock beside the staircase to “dong” and drop its minute hand to six o’clock.

Into this household, with his new bride, Elaine (Priscilla Lane), who, almost annoyingly, pops in and out of the proceedings, comes another nephew of the sisters, Mortimer (Cary Grant). After a while, so that things don’t become unduly settled, two criminals on the lam arrive, a drunken plastic surgeon, Dr. Einstein (Peter Lorre), and his hulking friend Jonathan Brewster (Raymond Massey). Whoops, another nephew! Jonathan, thanks to Einstein’s malpractice talents, has the face of Boris Karloff, not accidentally, as Warner Bros. refused the expense to obtain the English actor. Naturally, the next best thing is to make him look like Karloff. When Elaine sees Jonathan for the first time, she wails, “I suppose you’re going to tell me you’re Bor—“ and is interrupted.

An Irish policeman (Jack Carson) on his beat is often dropping by but has little clue as to what’s going on in the house, even when he finds Mortimer gagged and tied to a chair. Dr. Einstein explains away the truth by saying they were rehearsing a play. O’Hara, a budding playwright, swallows the lie and decides that, since Mortimer is a true “captive” audience, now would be a good time to regale him with the plot of his play.

An Irish policeman (Jack Carson) on his beat is often dropping by but has little clue as to what’s going on in the house, even when he finds Mortimer gagged and tied to a chair. Dr. Einstein explains away the truth by saying they were rehearsing a play. O’Hara, a budding playwright, swallows the lie and decides that, since Mortimer is a true “captive” audience, now would be a good time to regale him with the plot of his play.

Lieutenant Rooney (James Gleason), O’Hara’s boss, comes by toward the end and, typical of the other characters, he seems a bit—should I say it?—yes, a bit loony. No coincidence, perhaps, that his name rhymes with “loony.” Although giving the impression of the in-charge type, he is equally unintuitive and doesn’t recognize the criminal Dr. Einstein standing right before him as he repeats his description, given to him by someone on the telephone, even congratulating the doctor on helping the police nab Jonathan.

The Max Steiner score is surprisingly subdued for the composer. With any number of opportunities to fall in with the devil-may-care atmosphere of everything—the inflated acting, hectic pace, the macabre tone—old Max keeps the Mickey-Mousing to a minimum. He does manage a bright, tinkling, typical Steiner “traveling” theme for the sisters, which recalls the one for the fluttery Harriett Stanley in The Man Who Came to Dinner, made the same year. For Einstein and Jonathan, Steiner produces some ghoulish tones, which he would exploit in 1946 in The Beast with Five Fingers, one of his few forays into the horror genre.

The crisp black and white cinematography of Sol Polito, whose credits include The Petrified Forest, The Sea Hawk and Sergeant York, comes to the fore in some spooky, “dark night” scenes.

Aside from sporadic scenes on the sidewalk and in the cemetery next to the Brewster house, most of the action occurs in one room. It’s a typical stage setting, with handy entrances stage right (the front door) and stage left (a wide window above a body-changing window seat); against the back wall, the door to the kitchen (left center) and another door to the cellar (right center); and the stairs (extreme right) that stand in for Teddy’s San Juan Hill. As in a play, the characters are continually entering and exiting, especially through the front door in the last quarter of the film. All which reinforce the film’s stage origins.

Aside from sporadic scenes on the sidewalk and in the cemetery next to the Brewster house, most of the action occurs in one room. It’s a typical stage setting, with handy entrances stage right (the front door) and stage left (a wide window above a body-changing window seat); against the back wall, the door to the kitchen (left center) and another door to the cellar (right center); and the stairs (extreme right) that stand in for Teddy’s San Juan Hill. As in a play, the characters are continually entering and exiting, especially through the front door in the last quarter of the film. All which reinforce the film’s stage origins.

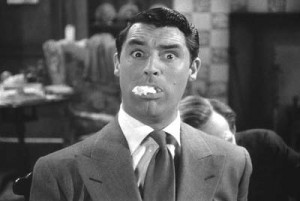

There are several reasons why Arsenic isn’t the equal of the three Capra films I mentioned. The wild pace of the film, though I easily settled into it, is due, first, to Capra having to shoot during eight weeks when the Broadway stars of the play (Hull, Adair and Alexander) were available. Second, the director was rushing to finish by the deadline for his enlistment in the U.S. Signal Corps (the bombing of Pearl Harbor occurred during filming). Grant is constantly mugging, with an annoying, frenzied delivery and numerous bug-eyed double takes at the camera. (He later would deem this his worst performance.) As in his previous films, Capra had planned to reshoot the weaker parts, as he sensed, for one, Grant’s overacting, but did not have the time.

There are several reasons why Arsenic isn’t the equal of the three Capra films I mentioned. The wild pace of the film, though I easily settled into it, is due, first, to Capra having to shoot during eight weeks when the Broadway stars of the play (Hull, Adair and Alexander) were available. Second, the director was rushing to finish by the deadline for his enlistment in the U.S. Signal Corps (the bombing of Pearl Harbor occurred during filming). Grant is constantly mugging, with an annoying, frenzied delivery and numerous bug-eyed double takes at the camera. (He later would deem this his worst performance.) As in his previous films, Capra had planned to reshoot the weaker parts, as he sensed, for one, Grant’s overacting, but did not have the time.