“I know that you don’t tell people a lot of things. . . . I have a feeling that inside you somewhere there’s something nobody knows about, something secret and wonderful. I’ll find out.”—— Charlie Newton (Teresa Wright) to Uncle Charlie

Whom would you like to invite for a visit? A high school classmate you haven’t seen in twenty-five years? A former suitor? A new acquaintance you met a few weeks ago? Better yet, what about a favorite uncle, the one your mother is always talking about, the one you were named after? And maybe you’re a little bored, in this town of yours where nothing ever happens. And suppose, while you’re thinking about this uncle, you hear from him, that he’s coming for a visit. You, of course, would hear most expediently by e-mail.

But in 1943, in Santa Rosa, California, a wall telephone would be the primary long-distance communication device, with the receiver on a stiff cord and the mouthpiece on the phone itself. Charlie Newton (Teresa Wright) learns from her little sister, Ann (Edna May Wonacott), who had answered the phone, that the family has a telegram at the postal union. All day, Charlie had been depressed, telling her father, Joe (Henry Travers), “This family’s gone to pieces. We just go along. Nothing ever happens. We’re in a rut.”

In fact, that very day she had been thinking of a solution—Uncle Charlie, that wonderful, favorite uncle back East, and when she reads the telegram that he’s coming for a visit, she tells the clerk the coincidence must be due to mental telepathy. “I only send telegrams the normal way,” the clerk (Minerva Urecal) replies. The girl had always believed there was a special bond between them. She had, after all, been named after him. He is her mother’s (Patricia Collinge) younger brother.

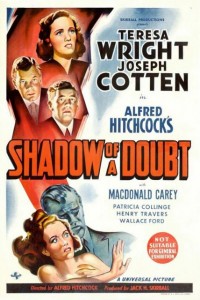

Viewers of Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt already know what young Charlie doesn’t know, that her beloved uncle, Charles Oakley ([intlink id=”140″ type=”category”]Joseph Cotten[/intlink]), isn’t all he seems to be. As he lies on the bed of a dingy boarding house in the film’s opening, the landlady tells him that two men have asked for him. She bends down to pick up the money carelessly strewn on the floor. When the two men appear across the street, Oakley leaves town, telegraphing young Charlie that he’s coming for a visit.

Viewers of Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt already know what young Charlie doesn’t know, that her beloved uncle, Charles Oakley ([intlink id=”140″ type=”category”]Joseph Cotten[/intlink]), isn’t all he seems to be. As he lies on the bed of a dingy boarding house in the film’s opening, the landlady tells him that two men have asked for him. She bends down to pick up the money carelessly strewn on the floor. When the two men appear across the street, Oakley leaves town, telegraphing young Charlie that he’s coming for a visit.

Some critics could argue that Hitch should not have suggested Oakley’s dubious nature in the beginning and, instead, begun with young Charlie reading the telegram, then the arrival of the uncle’s train. The first intimations that Uncle Charlie has a shadow, would then be his feigning illness—hiding in a sleeping berth of the train—and the cloud from the old steam locomotive of unusually black smoke, hovering ominously in the sky and engulfing the station, symbolic of the arrival of evil.

No. Better that Hitch’s vision remain, better by far. For one, as it is, Uncle Charlie’s disregard and disrespect for money, a secondary motif of the film, is immediately introduced. More important, the initiation of the primary motif of the double is launched with the two men “asking for him.”

Donald Spoto, in his masterpiece, The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock, enumerates the instances of the double in the film, “almost past counting”: two detectives in the East, two in Santa Rosa, two children in the family, two dinner sequences, two amateur sleuths, two attempts to kill the girl, two scenes in the garage, two waitresses, etc.; even the bar where the two Charlies have a confrontation is the Till Two. The disadvantage, however, of the author’s emphasis is that the viewer will over scrutinize the screen, for example, observing a candelabra in the background of a dinner scene and wondering why it has three candles instead of two! There’s a wondering, as well, about the reliability of Spoto’s portrait of Hitch’s character—was it as dark and paranoidly dual-sided as he paints it?

As the Newton family drives to the station to pick up Uncle Charlie, there’s an accompanying, sprightly “The Man on the Flying Trapeze”-type tune, but when the group walks from the train, back to the car, the uncle falling behind and alone on screen, the score segues into a subtle suggestion of Franz Lehár’s famous Merry Widow waltz.

As the Newton family drives to the station to pick up Uncle Charlie, there’s an accompanying, sprightly “The Man on the Flying Trapeze”-type tune, but when the group walks from the train, back to the car, the uncle falling behind and alone on screen, the score segues into a subtle suggestion of Franz Lehár’s famous Merry Widow waltz.

Hitchcock always knew exactly what he wanted in each of his carefully prepared films, and the nature and substance of the musical score was no different. Sound, whatever its nature, was vitally important. He had told his composer Dimitri Tiomkin that his score should—“would” is the proper word—be built around this particular waltz, often with a double exposure of dancing Victorians. In fact, this music and this image are behind the main title.

Uncle Charlie arrives at the quaint, two-story house—surely its being two-story is coincidental—with much nostalgia and love, especially the last from his naïve, all-adoring sister. As Emma, the mother of Charlie and two other siblings, she is one of Hitchcock’s few positive matriarchal portraits, endearingly so. Witness the self-righteous, scatter-brained, controlling or aggressive mother figures in any number of the director’s films—in Marnie, Strangers on a Train, The Birds, Notorious and on and on, even a “mother” who isn’t really there, controlling nonetheless, in Psycho.

Uncle Charlie arrives at the quaint, two-story house—surely its being two-story is coincidental—with much nostalgia and love, especially the last from his naïve, all-adoring sister. As Emma, the mother of Charlie and two other siblings, she is one of Hitchcock’s few positive matriarchal portraits, endearingly so. Witness the self-righteous, scatter-brained, controlling or aggressive mother figures in any number of the director’s films—in Marnie, Strangers on a Train, The Birds, Notorious and on and on, even a “mother” who isn’t really there, controlling nonetheless, in Psycho.

At the first dinner sequence in his sister’s home, Uncle Charlie passes out gifts—a mink stole for his sister, a wristwatch for her husband, a ring for young Charlie, a stuffed animal for Ann and a gun and holster set for Roger (Charles Bates). Young Charlie, humming the waltz from The Merry Widow, says she can’t place the tune. Emma says it’s Victor Herbert, Roger admonishes that “Victor Herbert” isn’t a waltz and Uncle Charlie promptly suggests On the Beautiful Blue Danube. Suddenly Charlie says, “I know. It’s the Merry—” Whereupon the uncle tips over a glass of water to disrupt the discussion.

The upset glass passes young Charlie’s notice but not her uncle’s folding and cutting the daily paper to make a play house for Ann. He tears off a strip for a door, but that piece isn’t in the waste paper basket with the discarded page. Checking the public library’s copy, young Charlie finds the missing part, a story about a so-called “Merry Widow” murderer who strangles rich widows; he has eluded police in the East and is believed to be on the West coast.

The upset glass passes young Charlie’s notice but not her uncle’s folding and cutting the daily paper to make a play house for Ann. He tears off a strip for a door, but that piece isn’t in the waste paper basket with the discarded page. Checking the public library’s copy, young Charlie finds the missing part, a story about a so-called “Merry Widow” murderer who strangles rich widows; he has eluded police in the East and is believed to be on the West coast.

This evidence isn’t conclusive enough for the girl, but other happenings only aggravate her suspicions. For one, the gift ring is inscribed with some unknown initials. Also, Uncle Charlie has an aversion to being interviewed or photographed by a two-man survey team seeking the “typical American family.” In a night scene on a Santa Rosa park bench, one of the men, Jack (MacDonald Carey), reveals that he and his partner, Fred (Wallace Ford), are actually detectives on the trail of a criminal from “back East” who might be her uncle.

Shadow of a Doubt introduced at least two new stars. Edna May Wonacott was an eleven-year-old daughter of a Santa Rosa grocer (Hitch’s father was a green grocer), and although her career was short and otherwise undistinguished, she represents the typical extra-bright child, resentful of that child’s stuffed animal and a reader of Ivanhoe, as Hitch was also an avid reader and knew much of the Scott novel by heart. Hume Cronyn is the other half, with Travers, of the pair of crime enthusiasts who theorize on the best way to kill one another. He would be in Hitch’s next film, Lifeboat, and contribute to a number of the director’s later scripts.

Shadow of a Doubt introduced at least two new stars. Edna May Wonacott was an eleven-year-old daughter of a Santa Rosa grocer (Hitch’s father was a green grocer), and although her career was short and otherwise undistinguished, she represents the typical extra-bright child, resentful of that child’s stuffed animal and a reader of Ivanhoe, as Hitch was also an avid reader and knew much of the Scott novel by heart. Hume Cronyn is the other half, with Travers, of the pair of crime enthusiasts who theorize on the best way to kill one another. He would be in Hitch’s next film, Lifeboat, and contribute to a number of the director’s later scripts.

Shadow of a Doubt is Hitchcock’s first truly American film, although the previous one, Saboteur, is an early cross-country version of North by Northwest. More important, it is also perhaps the director’s favorite film, not because of its authentic creation of an American community (exteriors were filmed in Santa Rosa), but because in no other film, before or after, does Hitch reveal so much of himself—his personal life at the time, his demons, his phobias, his negative view of the world, that dual personality so expressed in the treatment of the double. Most of the audience, no matter in which decade the film is seen, never suspects its autobiographical revelations.

The adoring mother Emma was named after Hitch’s own mother, who had died during filming. The director was further traumatized by the fate of his beloved England in a war still raging in Europe. In dialogue of his own, Hitch’s childhood bicycle accident is given to Uncle Charlie. Even the $40,000 the uncle deposits in the bank is the exact amount the director had just paid for a new home in Los Angeles.

His prudish Victorian morality—on the outside, at least—is expressed in Uncle Charlie’s idealized memory of that “wonderful world” of his and his sister’s childhood as contrasted with the current world as “a foul sty.” The uncle’s bar room tirade, which shatters any lingering illusions the young Charlie might have had about him, was also written by Hitch, ending: “Do you know, if you ripped the fronts off houses, you’d find swine? The world’s a hell! What does it matter what happens in it?”

His prudish Victorian morality—on the outside, at least—is expressed in Uncle Charlie’s idealized memory of that “wonderful world” of his and his sister’s childhood as contrasted with the current world as “a foul sty.” The uncle’s bar room tirade, which shatters any lingering illusions the young Charlie might have had about him, was also written by Hitch, ending: “Do you know, if you ripped the fronts off houses, you’d find swine? The world’s a hell! What does it matter what happens in it?”

As Spoto so brilliantly relates in his book—required reading for all Hitchcockians: “He considered all life unmanageable, and his obsessive neatness (like his careful preparation of a film) was a way of taking a stand against the chaos he believed was always at the ready . . . Meticulous at work, he was cavalier and reckless about his health. [He was perhaps at his heaviest, 300 pounds, during Shadow of a Doubt filming.] Proper in public, he was inclined, if there was no microphone present, to outrageous toilet humor.”

Although the film is his best example of the handsome and charming villain, Hitch didn’t hesitate to plan a diabolical fate for Uncle Charlie, perhaps as a kind of secret revenge. He always devised special ends for his villains—even for some of the good characters. If not strangulation, his favorite method of dispatch, then a fall would do the trick—through a glass roof in the British Museum in Blackmail, off the Statue of Liberty in Saboteur, from a church tower in Vertigo or from Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest. In Shadow of a Doubt, a fall from a moving train into the path of another would be the fate of that visitor from the East.

Poor Uncle Charlie. In the film’s brief epilogue, as the young niece says to Jack, he and she having by now become enamored, “He thought the world was a horrible place. He couldn’t have been very happy, ever. He didn’t trust people. . . . He said that people like us had no idea what the world was really like.”

Hitchcock’s favorite of his films and by a long ways mine too. A small masterpiece. The interweaving of story is masterful. I understand that even the actress who played the mother added her own ideas about how to develop the story and what her character should be like.

Can’t end this without mentioning Teresa Wright, and he so very subtle portrait of the other “Charlie.” She had done some stage work and had already one two oscars for supporting roles in Mrs Miniver and the Lou Gehrig Story.”

Somehow she “slipped” through the fingers of a fickle public. Probably because she was not the “babe” type so popular then. Instead, she was more the “girl next door” type and there were not many vehicles for that type of actress.

Strangely, she made a second film with Joseph Cotton some years later, playing his wife — he tries to pull off an inside job bank robbery, but fails. It is not a very good movie, but interesting to see her is B material.

Also, she appeared in “Track of the Cat” based on the Walter Van Tillborg novel. She plays a domestic sister to Robert Mitchum who is determined to hunt down a troublesome (and symbolic) panther.

That was about the end of her career, except she played a woman in a rather recent film. Small role, Sorry that I can not remember the name of it. And she is on screen about five minutes, and of course she has aged. No longer the young woman in Shadow, but when she talks her voice has not changed. But to see her in these other “less than stellar’ films is disconcerting, since she so strongly embodies the role of Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt. Not one to be missed.

Perhaps the “slap in the face” stipulations of her contractual obligations might have had a role in her filmic future!

Echo! Both “Young Charlie” and “Uncle Charlie” are two peas in a pod. Murderers.