The borrowing of the Wagner brings up the hypothesis, suggested by many individuals, that “Herrmann couldn’t write a melody if he had to.” He could—in his fashion. What about, for example, the “Nocturne” from White Witch Doctor as possessing a legitimate melody? There is, too, the “Romance on the Train” the long, sexy sequence between Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint in North by Northwest, an undulating, presumably “traveling” dialogue between oboe and clarinet, followed by the strings. Similarly, a valse triste appears in a number of scores, and one of the best is the “Memory Waltz” from The Snows of Kilimanjaro. But fellow film composer David Raksin (Laura, The Bad and the Beautiful) disagrees: “If Benny ever started a tune, as in the case of the ‘Memory Waltz,’ he would obliterate it in no time at all.” Author Smith, perhaps correctly, asserted a middle ground: “ . . . while his melodic facility was limited, Herrmann could write themes of lyric poignancy and unpretentious charm.”

The borrowing of the Wagner brings up the hypothesis, suggested by many individuals, that “Herrmann couldn’t write a melody if he had to.” He could—in his fashion. What about, for example, the “Nocturne” from White Witch Doctor as possessing a legitimate melody? There is, too, the “Romance on the Train” the long, sexy sequence between Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint in North by Northwest, an undulating, presumably “traveling” dialogue between oboe and clarinet, followed by the strings. Similarly, a valse triste appears in a number of scores, and one of the best is the “Memory Waltz” from The Snows of Kilimanjaro. But fellow film composer David Raksin (Laura, The Bad and the Beautiful) disagrees: “If Benny ever started a tune, as in the case of the ‘Memory Waltz,’ he would obliterate it in no time at all.” Author Smith, perhaps correctly, asserted a middle ground: “ . . . while his melodic facility was limited, Herrmann could write themes of lyric poignancy and unpretentious charm.”

All right, so melody wasn’t Herrmann’s forte. Melodies occupy time and screen space, often the action moves on before a bona fide tune can unfold properly and emotions/actions/visuals change intermittently. Herrmann, who did his own orchestration, a rarity in Hollywood, used as his basic musical tools motifs and ostinatos, sometimes nothing more than a favorite interval, repeated incessantly, with changes in instruments and key. One of my favorite Herrmann scores is Journey to the Center of the Earth, a cardboard frolic as a film, yes, but the music——! It’s unbelievably effective—and so simple—when James Mason is melting the crust off a piece of lava which he feels has something much heavier inside. The furnace suddenly explodes. Before this, the long dialogue scene had been without music; immediately after the blast, amid smoke and with Mason now on the floor, a two-note phrase is repeated in the lowest registers of the orchestra. (I’ve often wondered if the rolling boulder in Journey was not the inspiration for the one in Raiders of the Lost Ark.)

One incident related in A Heart at Fire’s Center requires mention—in this case showing Benny’s meticulousness. In 1974 Charles Gerhardt and the National Philharmonic Orchestra of London were in the midst of RCA’s Classic Film Score series and were recording an LP devoted to excerpts from five Herrmann scores. Gerhardt relates the preparations for White Witch Doctor :

Benny drove everybody crazy, because he wanted just the right sound for the clang in the opening. . . . He finally ended up using [an automobile] brake drum . . . Tris Frye, the head of percussion, . . . brought brake drums to the session, plus an enormous anvil which weighed a ton—all this to just try things. Here we were, waiting to record the main title, and Benny was over in the percussion section clanking away. We had one from a Rolls Royce; that didn’t make it. Then one from a Volkswagen—and Benny said, “That’s it!” It was as if an oboe player were changing his reed.

Despite the money he earned from his film scoring and that movie music would become the source of his fame, his goal in life was to acquire an appointment as permanent conductor of a famous orchestra. Conducting was the one thing in the world he loved most. At one point, he felt he had prospects with the London Philharmonic, with which he made many guests appearances and recorded some of his best classical albums, but he was ignored. For a while he was quite popular with a number of orchestras in England, where he lived and worked during the last years of his life, but the flare-ups of Herrmannian ego, tantrums and verbal abuse eventually became intolerable.

As time passed and Herrmann’s health began to fail, Hollywood was quickly changing. Rich, wall-to-wall scores that had begun with Korngold, Max Steiner and Franz Waxman were out. Jazz became the vogue, then, more and more, producers and directors wanted hit title songs and popular music throughout their films.

Work became scarce, and Torn Curtain marked, after eight films, Herrmann’s last collaboration with Hitchcock. Hitch had specified what he wanted in the score, but Herrmann disregarded most of what he said, using a huge orchestra, including twelve flutes and sixteen French horns! The director rejected the score in favor of a conservative one by John Addison. As Benny told the director, “Look, Hitch, you can’t out jump your own shadow. And you don’t make pop pictures. What do you want with me? I don’t write pop music.”

Work became scarce, and Torn Curtain marked, after eight films, Herrmann’s last collaboration with Hitchcock. Hitch had specified what he wanted in the score, but Herrmann disregarded most of what he said, using a huge orchestra, including twelve flutes and sixteen French horns! The director rejected the score in favor of a conservative one by John Addison. As Benny told the director, “Look, Hitch, you can’t out jump your own shadow. And you don’t make pop pictures. What do you want with me? I don’t write pop music.”

Torn Curtain

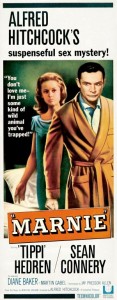

[audio:http://www.classicfilmfreak.com/audio/torn curtain.mp3] As both Hitchcock’s and Herrmann’s careers peaked around the same time, in the 1950s, early ’60s, so their respective “touches” declined concurrently. Marnie, after The Birds, was the beginning of Hitch’s decline, and the score conveyed an unsettling sense that the composer was starting to borrow from himself. In between Marnie and Torn Curtain there had been the dismal—as a movie and as a score—Joy in the Morning, an insipidly written and acted love story between the then popular Richard Chamberlain and Yvette Mimieux.

As both Hitchcock’s and Herrmann’s careers peaked around the same time, in the 1950s, early ’60s, so their respective “touches” declined concurrently. Marnie, after The Birds, was the beginning of Hitch’s decline, and the score conveyed an unsettling sense that the composer was starting to borrow from himself. In between Marnie and Torn Curtain there had been the dismal—as a movie and as a score—Joy in the Morning, an insipidly written and acted love story between the then popular Richard Chamberlain and Yvette Mimieux.

Marnie

[audio:http://www.classicfilmfreak.com/audio/marnie.mp3]Although Herrmann’s score was the best thing about François Truffaut’s failed Fahrenheit 451, thereafter, between 1968 and 1975, he scored only six films, most of them Grade B horror films, all of the quality he would have rejected fifteen years earlier, e.g., The Bride Wore Black, The Night Digger, The Battle of Neretva, Endless Night, Sisters and It’s Alive!

His next-to-last score, Obsession was, again, something of a recycling of old ideas, although there were magical moments reminiscent of Herrmann at his best, for example “The Ferry.” In his last work, Taxi Driver, as the composer didn’t write jazz, Benny asked Christopher Palmer for help, so the film’s most famous theme is only partly Herrmann’s.

Two hours after recording the last of the Taxi Driver score to film, the composer died at his London home, Christmas Eve, 1975.

Thought the Theramin Paced Dali in the 1948 “Spellbound”?