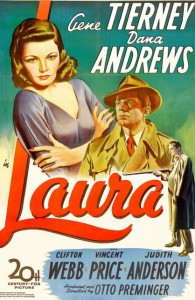

Despite these generally well done commentaries, sometimes, lurking behind the screens, there are the voices of less enjoyable, less suitable individuals discussing the art of movies. One occurs in Laura, one of the great film noirs of the 1940s. Not technically a true joint effort, Jeanine Basinger, a professor at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, gushes and oohs and aahs, sometimes becoming painfully cutesy, while composer David Raksin makes guarded insertions. There’s no interaction between the two, simply because he was recorded at another time, his disemboweled voice emerging whenever Basinger catches her breath. Although Raksin gets a few words in edgewise about his music, it’s clear he’s on a tight rein. An unfortunate situation, as Raksin created a haunting score, something of a milestone. One excellent source of information is the late composer’s erudite liner notes for a possibly still available RCA CD of Raksin conducting some of his best music, from Laura, The Bad and the Beautiful and Forever Amber. As an escape from Basinger, on the Laura DVD there is also a separate commentary by Rudy Behlmer.

Despite these generally well done commentaries, sometimes, lurking behind the screens, there are the voices of less enjoyable, less suitable individuals discussing the art of movies. One occurs in Laura, one of the great film noirs of the 1940s. Not technically a true joint effort, Jeanine Basinger, a professor at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, gushes and oohs and aahs, sometimes becoming painfully cutesy, while composer David Raksin makes guarded insertions. There’s no interaction between the two, simply because he was recorded at another time, his disemboweled voice emerging whenever Basinger catches her breath. Although Raksin gets a few words in edgewise about his music, it’s clear he’s on a tight rein. An unfortunate situation, as Raksin created a haunting score, something of a milestone. One excellent source of information is the late composer’s erudite liner notes for a possibly still available RCA CD of Raksin conducting some of his best music, from Laura, The Bad and the Beautiful and Forever Amber. As an escape from Basinger, on the Laura DVD there is also a separate commentary by Rudy Behlmer.

Basinger as a so-called “scholar” brings up the legitimacy of this breed discussing films. In Lifeboat (Drew Casper), Notorious (Marian Keane) and The Bride of Frankenstein (Scott MacQueen), to cite only a few examples, these scholars, critics and academics, if also sometimes short on enthusiasm, are a bit dry, reading, as they often do, from a text. The director of The Day the Earth Stood Still, Robert Wise, is not so much interviewed as interrogated by a sometimes confrontational, sometimes know-it-all Nicholas Meyer, who talks almost as much as his guest, sometimes anticipating Wise’s answers. Meyer, however, redeems himself in numerous other areas. In one, he concocted a fine addition to the unofficial Sherlock Holmes canon, his novel The Seven Percent Solution, which was made into a quite decent movie with Nicol Williamson.

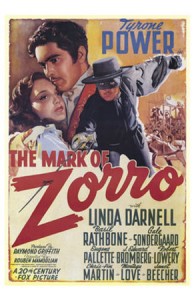

Oh, these critics! One wonders why Richard Schickel took on the task of commenting on The Mark of Zorro, for his approach comes across as just that, an annoying task. He is intuitive enough to notice the poignancy and superb photography (Arthur Miller) in the chapel scene between Lolita (Linda Darnell) and Zorro (Tyrone Power), disguised as a padre. But in many other instances, Schickel is generally aloof, almost singsongish and unnecessarily condescending, using such phrases as “in these types of films,” as if bacterially infected. He belittles the incompetence of the bad guys frantically running around in a garden in search of Zorro. Well, “in these types of films,” sir, the villains are supposed to let the hero bolt; these are escapist adventure movies, not Hamlet-like dramas. In his introductory comments, Schickel refers to the “prehistory” of Zorro! What is history if it’s not “pre”?! Anthony Adverse, by the way, was made in 1936, not 1934. Or is that nitpicking? Yes, definitely nitpicking.

Oh, these critics! One wonders why Richard Schickel took on the task of commenting on The Mark of Zorro, for his approach comes across as just that, an annoying task. He is intuitive enough to notice the poignancy and superb photography (Arthur Miller) in the chapel scene between Lolita (Linda Darnell) and Zorro (Tyrone Power), disguised as a padre. But in many other instances, Schickel is generally aloof, almost singsongish and unnecessarily condescending, using such phrases as “in these types of films,” as if bacterially infected. He belittles the incompetence of the bad guys frantically running around in a garden in search of Zorro. Well, “in these types of films,” sir, the villains are supposed to let the hero bolt; these are escapist adventure movies, not Hamlet-like dramas. In his introductory comments, Schickel refers to the “prehistory” of Zorro! What is history if it’s not “pre”?! Anthony Adverse, by the way, was made in 1936, not 1934. Or is that nitpicking? Yes, definitely nitpicking.

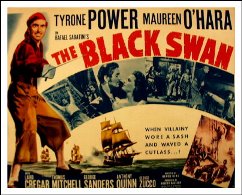

In another Power film, The Black Swan, it is the guest who upstages the fact-heavy, page-turning Rudy Behlmer and transforms a possible routine experience into a joy. Maureen O’Hara, in her mid-eighties at the time of the interview, sounds half that age, charming and exuberantly sharing the glory years of Hollywood. She confesses she and co-star Power shared a love of ice cream and were late to the studio after a stopover at a favorite ice cream haunt. Totally unaffected, she’s sincerely gracious toward her cameraman Leon Shamroy and his “cool” color photography and toward fellow actors Thomas Mitchell, Power and the larger-than-life Laird Cregar, who, she sadly relates, died from—it sounded like to me—an operation gone wrong.

In another Power film, The Black Swan, it is the guest who upstages the fact-heavy, page-turning Rudy Behlmer and transforms a possible routine experience into a joy. Maureen O’Hara, in her mid-eighties at the time of the interview, sounds half that age, charming and exuberantly sharing the glory years of Hollywood. She confesses she and co-star Power shared a love of ice cream and were late to the studio after a stopover at a favorite ice cream haunt. Totally unaffected, she’s sincerely gracious toward her cameraman Leon Shamroy and his “cool” color photography and toward fellow actors Thomas Mitchell, Power and the larger-than-life Laird Cregar, who, she sadly relates, died from—it sounded like to me—an operation gone wrong.

Although the cinematographer Jack Cardiff paints a near-terrifying picture of tangled jungles and rampant creatures during The African Queen shoot, it appears that directors have an inside track on insight, as suggested earlier by the expertise of Petersen and Mulligan. Here are some of my favorites, all topnotch, I think. John McTiernan is almost self-critical in discussing The Hunt for Red October, mentioning Sean Connery’s problems with his Russian and wondering if viewers can distinguish between American and Russian submarines by the different colored lighting of their interiors.

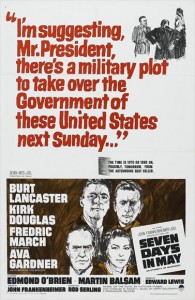

In Seven Days In May, John Frankenheimer is a natural for telling interesting stories—almost hilariously so when he recounts detouring a group of legitimate demonstrators headed for the White House, so he would have enough time to film his own extras rioting in front of the famous residence. Ava Gardner, he says, is sometimes a difficult actress. He points out the worst line in all his films, one he regrets never deleting, a line spoken by Ava to Kirk Douglas: “I’ll make you two promises—a very good steak medium rare and the truth, which is very rare.” Fascinating is the tale of his own favorite painting he ordered on the set to replace one he didn’t like; his ex-wife saw the movie and sued for the painting! And Frankenheimer praises the dedication and professionalism of Fredric March and Burt Lancaster who spent several weekends rehearsing their big confrontation scene.

In Seven Days In May, John Frankenheimer is a natural for telling interesting stories—almost hilariously so when he recounts detouring a group of legitimate demonstrators headed for the White House, so he would have enough time to film his own extras rioting in front of the famous residence. Ava Gardner, he says, is sometimes a difficult actress. He points out the worst line in all his films, one he regrets never deleting, a line spoken by Ava to Kirk Douglas: “I’ll make you two promises—a very good steak medium rare and the truth, which is very rare.” Fascinating is the tale of his own favorite painting he ordered on the set to replace one he didn’t like; his ex-wife saw the movie and sued for the painting! And Frankenheimer praises the dedication and professionalism of Fredric March and Burt Lancaster who spent several weekends rehearsing their big confrontation scene.

Lancaster also ties in with Delbert Mann. Director and actor made a number of first-class films together: The Train, Birdman of Alcatraz, The Young Savages—and Separate Tables. In the last, Mann details his efforts to get the actor to suppress a typical, often-seen fist gesture which never completely disappears despite some eighteen takes. After Mann selects what he feels is the least idiosyncratic of the takes, Lancaster replaces it with the one he prefers. Seems Lancaster’s company, Hill-Hecht-Lancaster Productions, which was producing the film, took control of the final edit, and the actor made this and some critical changes in the film. Mann finds the British to be the most professional of actors, David Niven full of endless, funny stories. With admiration and sympathy, he describes Gladys Cooper’s failing memory and deformed, arthritic fingers, and how often she had to film a scene closing a series of folding, glass-paneled doors while saying her lines. “A wonderful person.”

Both Frankenheimer and Mann give thoroughly comfortable deliveries, impressively anecdotal and spontaneous.

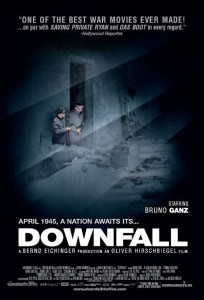

Among director commentaries, almost in a class by itself, is Oliver Hirschbiegel’s for his German language film Downfall (Der Untergang), the best version, so far, of Hitler’s last days in the bunker. Besides more than the expected details about the filming itself, the director shares his insights into the working of this evil man. “He didn’t care about anybody or anything, not even himself. Hitler’s whole life was about destruction.” Hirschbiegel has what most of these directors have, especially the last two I mentioned—a relaxed, unpretentious and unscripted delivery, a model among commentaries, with possibly only one or two rivals.

Among director commentaries, almost in a class by itself, is Oliver Hirschbiegel’s for his German language film Downfall (Der Untergang), the best version, so far, of Hitler’s last days in the bunker. Besides more than the expected details about the filming itself, the director shares his insights into the working of this evil man. “He didn’t care about anybody or anything, not even himself. Hitler’s whole life was about destruction.” Hirschbiegel has what most of these directors have, especially the last two I mentioned—a relaxed, unpretentious and unscripted delivery, a model among commentaries, with possibly only one or two rivals.

When hearing these commentaries, I always wonder about those directors who passed on long before the development of the DVD. How would they have approached analyzing, dissecting, hindsighting, maybe rationalizing their films—and how well would they have done? I’m especially curious about what secrets some of my favorite directors might have revealed about themselves and their art. Would William Wyler’s taskmaster style come across? Just to hear John Huston, who was a near-genius—just that voice! And John Ford. He wouldn’t reveal much, if anything, because he never talked about the aesthetics of movie-making, nor how and why he did things.