Sim, in the beginning, with that recurring bit about the humbuggery of Christmas, has the empty-eyed look of a man who is unhappy, dispassionate and even sinister, and, yes, unkind. The scraggly, white hair and bald head, the stooped shoulders and the awkward gait only add to the image of a man lost unto himself. In the end, his transformation into a caring and now compassionate soul is not only something of a miracle in the context of the story—for a miracle is exactly what Dickens would have us believe—but the makeover Sim is able to convey is quite convincing, not silly, though perhaps a little too animated. His exuberance, however, is justified, for he, like us the viewer, the sharer of his experiences, has been through a good deal of dark foreboding in the previous eighty minutes or so. The whole premise of this transformation hinges on whether or not you believe people can change their essential natures, regardless the circumstances, especially someone like Scrooge who has lived a selfish, self-centered life for sixty or more years.

Sim, in the beginning, with that recurring bit about the humbuggery of Christmas, has the empty-eyed look of a man who is unhappy, dispassionate and even sinister, and, yes, unkind. The scraggly, white hair and bald head, the stooped shoulders and the awkward gait only add to the image of a man lost unto himself. In the end, his transformation into a caring and now compassionate soul is not only something of a miracle in the context of the story—for a miracle is exactly what Dickens would have us believe—but the makeover Sim is able to convey is quite convincing, not silly, though perhaps a little too animated. His exuberance, however, is justified, for he, like us the viewer, the sharer of his experiences, has been through a good deal of dark foreboding in the previous eighty minutes or so. The whole premise of this transformation hinges on whether or not you believe people can change their essential natures, regardless the circumstances, especially someone like Scrooge who has lived a selfish, self-centered life for sixty or more years.

Sim is supported by some great stars who for many people lie just beyond the perimeter of familiarity. The following are, let’s note, some of my favorite supporting actors. Hermione Baddeley, who plays Mrs. Cratchit, would later appear in Room at the Top, Midnight Lace with Doris Day and Rex Harrison and two musicals in 1964—Mary Poppins with Julie Andrews and The Unsinkable Molly Brown with Debbie Reynolds.

Michael Hordern had a long and varied career—his was the first death in Theater of Blood [see our review of Theater of Blood HERE] —but it seems A Christmas Carol kept cropping up. As Marley’s ghost in 1951, he warned Alastair Sim of the consequences of continuing his greedy and selfish life, in 1971 he was the voice of Marley in a British TV short and finally in 1977 Scrooge in a BBC TV movie. He’d moved up the ladder, or was it down? His career was dotted by, in particular, a variety of historical and period movies: Alexander the Great, Khartoum, El Cid, Sink the Bismarck!, Cleopatra (1963), Anne of the Thousand Days and Barry Lyndon.

Michael Hordern had a long and varied career—his was the first death in Theater of Blood [see our review of Theater of Blood HERE] —but it seems A Christmas Carol kept cropping up. As Marley’s ghost in 1951, he warned Alastair Sim of the consequences of continuing his greedy and selfish life, in 1971 he was the voice of Marley in a British TV short and finally in 1977 Scrooge in a BBC TV movie. He’d moved up the ladder, or was it down? His career was dotted by, in particular, a variety of historical and period movies: Alexander the Great, Khartoum, El Cid, Sink the Bismarck!, Cleopatra (1963), Anne of the Thousand Days and Barry Lyndon.

His face much concealed behind an enormous beard, Francis De Wolff, as the Spirit of Christmas Present, demonstrated his own versatility in Fire Over England with Vivien Leigh, Disney’s Treasure Island, Moby Dick, Ivanhoe and the Hammer production of The Hound of the Baskervilles (as Dr. Mortimer) with Peter Cushing.

His face much concealed behind an enormous beard, Francis De Wolff, as the Spirit of Christmas Present, demonstrated his own versatility in Fire Over England with Vivien Leigh, Disney’s Treasure Island, Moby Dick, Ivanhoe and the Hammer production of The Hound of the Baskervilles (as Dr. Mortimer) with Peter Cushing.

In the last film, as the bishop arachnologist, was Miles Malleson. In the Sim Christmas Carol, he was Old Joe, the thief in the flashback with the Spirit of Christmas Yet to Come. He played the hangman of Dennis Price in Kind Hearts and Coronets, a show stolen, however, by the multi-roled Alec Guinness. Malleson had other bit parts in Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (which also starred Alastair Sim), First Men in the Moon and as yet another bishop in Murder Ahoy See HERE for our review of the Margaret Rutherford/Agatha Christie mysteries.

In the last film, as the bishop arachnologist, was Miles Malleson. In the Sim Christmas Carol, he was Old Joe, the thief in the flashback with the Spirit of Christmas Yet to Come. He played the hangman of Dennis Price in Kind Hearts and Coronets, a show stolen, however, by the multi-roled Alec Guinness. Malleson had other bit parts in Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (which also starred Alastair Sim), First Men in the Moon and as yet another bishop in Murder Ahoy See HERE for our review of the Margaret Rutherford/Agatha Christie mysteries.

Ernest Thesiger—the undertaker in the Sim Christmas tale—made one of the most macabre, emaciated appearances in filmdom, that of Doctor Pretorius, with his “little people,” in The Bride of Frankenstein. He did service in another horror film, The Old Dark House, in good company with Charles Laughton, Melvyn Douglas, Gloria Stuart, Boris Karloff and Raymond Massey. There was also The Robe, Quentin Durward and the 1945 Caesar and Cleopatra, with Thesiger as Theodotus.

Peter Bull was one of two businessmen Scrooge encountered in the opening of the film. Bull, in fact, spoke the first words as well as narrated. He appeared in The African Queen, Dr. Strangelove, Tom Jones and The Lavender Hill Mob. Like Hordern, he had an ongoing Dickens connection, starring in David Lean’s Oliver Twist, in a BBC TV series The Pickwick Papers, in one episode of Fredric March Presents Tales from Dickens and in the ITC TV movie of Great Expectations (my favorite Dickens novel) as Mr. Wemmick.

Peter Bull was one of two businessmen Scrooge encountered in the opening of the film. Bull, in fact, spoke the first words as well as narrated. He appeared in The African Queen, Dr. Strangelove, Tom Jones and The Lavender Hill Mob. Like Hordern, he had an ongoing Dickens connection, starring in David Lean’s Oliver Twist, in a BBC TV series The Pickwick Papers, in one episode of Fredric March Presents Tales from Dickens and in the ITC TV movie of Great Expectations (my favorite Dickens novel) as Mr. Wemmick.

Aren’t the names of Dickens’ characters a riot? Just consider these, outside of Carol: Tattycoram, Blimber, Sweedlepipe, Jarndyce, Meagles and Micawber. (My spell-check flagged everyone of those names and would have done so on “Pumblechook,” if I’d used it!) Personally, I believe Dickens (1812-1870) gave his characters such names, and sometimes described them so grotesquely and in occasional non-human terms, because, contradictory as it may seem, he loved people. He must have love mankind in general: he was constantly crusading on its behalf, against its accumulative misfortunes and injustices.

Most of his novels have such themes. In Bleak House, Dickens protests the chancery courts of his time and the evils of money; in Hard Times, the materialistic educators; in Little Dorrit, convoluted government bureaucracy; and in Oliver Twist, though it made a fine musical in the early ’60s, the pervasive crime and poverty, the horrors of the work houses and child labor in the mid-nineteenth century. Walter Allen in his study The English Novel, wrote of Dickens’ command of characterization and his understanding of people:

Most of his novels have such themes. In Bleak House, Dickens protests the chancery courts of his time and the evils of money; in Hard Times, the materialistic educators; in Little Dorrit, convoluted government bureaucracy; and in Oliver Twist, though it made a fine musical in the early ’60s, the pervasive crime and poverty, the horrors of the work houses and child labor in the mid-nineteenth century. Walter Allen in his study The English Novel, wrote of Dickens’ command of characterization and his understanding of people:

“The child’s view of human beings is not less real than the adult’s, and it is the child’s that Dickens captures so unerringly. He catches with merciless delight the externals, the apparently meaningless gestures and nervous tricks we all have without knowing we have them, and he catches, too, the habits of speech, repetitions of favorite words and phrases, obsessional harpings on single themes whose victims we all tend unconsciously to be and which, taken together, make us in some degree walking caricatures of ourselves.”

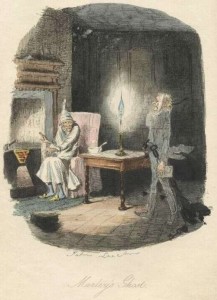

And the theme of A Christmas Carol? Although it has various references to Christianity—some viewers may see in the three Spirits of Christmas a possible allusion to the Trinity and in Marley’s return the resurrection of Jesus—Dickens’ message is much broader than that: it simply says be kind to one another and do good for those less fortunate. Not from me, but rather hear from Dickens what he puts in the mouth of Jacob Marley (quoting the novella, now) in his confrontation with Scrooge:

And the theme of A Christmas Carol? Although it has various references to Christianity—some viewers may see in the three Spirits of Christmas a possible allusion to the Trinity and in Marley’s return the resurrection of Jesus—Dickens’ message is much broader than that: it simply says be kind to one another and do good for those less fortunate. Not from me, but rather hear from Dickens what he puts in the mouth of Jacob Marley (quoting the novella, now) in his confrontation with Scrooge:

“ . . . in life, my spirit never roved beyond the narrow limits of our money-changing hole . . . Business! Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence were all my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

0 thoughts to “A Christmas Carol”